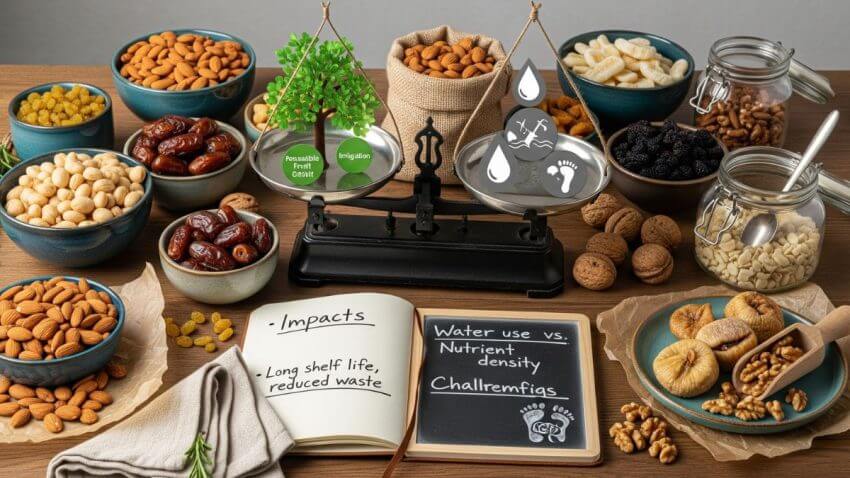

In an era of conscious consumerism, we increasingly ask where our food comes from and what its environmental and social impact is. Dry fruits, often perceived as natural and wholesome, are a fascinating case study in the complexities of food sustainability. The sustainability of dry fruits as a food source is a nuanced issue, balancing their incredible benefit of reducing food waste through long shelf life against significant environmental challenges in their production, such as high water and energy use. This article provides a balanced introductory overview of this topic. We will define what makes a food source sustainable, explore the inherent advantages of dry fruits, and examine the serious challenges facing their production. By presenting the trade-offs based on scientific evidence, this guide aims to move beyond a simple “good” or “bad” label, setting the stage for a deeper understanding of how our choices can support a more sustainable food system.

Defining Our Sustainability Focus

This article serves as a foundational overview of the sustainability profile of the dry fruit category. We will introduce the key benefits and challenges to provide a balanced perspective. For a more granular analysis of specific issues, please explore our deep dives into the Water Footprint of Major Dry Fruits and the Carbon Footprint of the Dry Fruit Industry. Our goal here is to build a foundational understanding of the complex issues involved.

Key Takeaways

- A Double-Edged Sword: Dry fruits present a significant sustainability paradox. Their long shelf life drastically reduces food waste compared to fresh fruit, but their production can be highly resource-intensive.

- The Biggest Pro – Reducing Waste: By extending the usability of a harvest from days to months, drying is a powerful tool against food spoilage, which is a major global environmental problem.

- The Biggest Con – Resource Intensity: The production of certain nuts and fruits, particularly almonds in arid regions, is extremely water-intensive. Furthermore, artificial drying methods are energy-intensive.

- Monoculture is a Key Challenge: Large-scale orchards often rely on monoculture (growing a single crop), which can reduce biodiversity and soil health compared to more integrated farming systems.

- Consumer Choice Matters: Supporting brands with certifications like USDA Organic and Fair Trade, and practicing portion control to avoid personal waste, are key ways consumers can promote a more sustainable dry fruit industry.

Historical and Cultural Significance of Dry Fruits

Dry fruits have been sustaining civilizations for over 4,000 years, representing one of humanity’s earliest and most successful food preservation technologies. Archaeological evidence from Mesopotamia and ancient Persia reveals that fruit drying techniques were developed around 2000 BCE, primarily as a survival strategy for long winters and desert trade routes. Understanding how consumption patterns evolved reveals the deep connection between sustainability practices and human civilization development.

The Silk Road traders carried dried apricots, dates, and figs across continents, establishing the first global dry fruit trade networks. Persian merchants introduced pistachios to Mediterranean cultures, while Indian traders brought cashews and almonds to European markets through ancient spice routes.

Today, dry fruits maintain deep cultural significance across religions and traditions. During Diwali, Indian families exchange boxes of mixed dry fruits as symbols of prosperity. Ramadan iftar tables feature dates as the traditional fast-breaking food, following Prophet Muhammad’s practice. Persian Nowruz celebrations include seven dried items representing renewal and abundance.

Beyond major religious observances, dry fruits carry symbolic meaning in diverse cultural contexts. Chinese New Year celebrations feature red dates (jujubes) representing good luck and sweet life ahead. European Christmas traditions incorporate dried fruits in stollen bread and fruitcakes, symbolizing preserved sweetness through winter months. Jewish Passover seders include dried fruits in charoset, representing the mortar used by enslaved ancestors in Egypt. Mediterranean cultures view dried figs as symbols of abundance and fertility, often included in wedding ceremonies and harvest festivals.

This cultural integration demonstrates how sustainable food practices can become deeply embedded in human society, creating emotional and spiritual connections that transcend mere nutrition.

What Does a “Sustainable Food Source” Actually Mean?

A sustainable food source is one that can be produced in a way that meets the nutritional needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. A sustainability scientist would explain that this concept rests on three interconnected pillars:

- Environmental Sustainability: This involves practices that protect natural resources, maintain biodiversity, and have a minimal negative impact on air, water, and soil.

- Social Sustainability: This relates to the ethical treatment of labor, ensuring safe working conditions and fair wages for farmers and workers throughout the supply chain.

- Economic Sustainability: This means that the farming and business practices are economically viable for farmers and producers, allowing them to maintain their livelihoods over the long term.

A food is rarely “perfectly” sustainable. Instead, sustainability is a spectrum, and understanding where dry fruits fall on this spectrum requires looking at both their benefits and their drawbacks.

Nutritional Profile and Health Benefits of Dry Fruits

Dry fruits represent some of nature’s most nutrient-dense foods, concentrating vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants into convenient, shelf-stable packages. The dehydration process removes water while retaining most essential nutrients, creating foods with exceptional nutritional value per gram.

Research published in the Journal of Nutritional Science demonstrates that nutrient concentration in dried fruits can be 3-5 times higher than fresh equivalents. Raisins contain concentrated iron and potassium, supporting blood health and muscle function. Almonds provide exceptional vitamin E levels, protecting cells from oxidative stress. Walnuts offer plant-based omega-3 fatty acids crucial for brain health.

Harvard School of Public Health studies indicate that regular dry fruit consumption correlates with reduced risks of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. The fiber content in dried fruits supports digestive health, while their natural antioxidants combat inflammation. However, portion control remains essential due to concentrated caloric density.

Dry Fruits in Different Dietary Approaches

The versatility of dry fruits makes them valuable additions to virtually every dietary pattern, from ancient traditional diets to modern specialized eating plans. Mediterranean diet research shows that regular nut and dried fruit consumption contributes to longevity and reduced chronic disease risk. The diet’s emphasis on whole foods, healthy fats, and plant-based nutrients aligns perfectly with dry fruit nutritional profiles.

Vegan and vegetarian diets benefit from dry fruits like almonds, which provide protein and B-vitamins, and cashews, which are rich in iron. Cashews and almonds provide essential amino acids often limited in plant-based diets. Paleo diet adherents rely on nuts and seeds as primary fat sources, avoiding processed foods while maintaining nutrient density.

Gluten-free diets utilize almond flour, cashew flour, and other nut-based alternatives for baking and cooking. Ketogenic dieters value the high-fat, low-carb profile of macadamias, pecans, and Brazil nuts. Even specialized medical diets like DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) incorporate unsalted nuts for their potassium and magnesium content.

Types of Dry Fruits and Their Nutritional Profiles

Understanding the diverse categories of dry fruits and their unique nutritional characteristics enables informed selection based on specific health goals and dietary requirements. Classification systems typically organize dry fruits by botanical origin, processing method, and nutritional composition.

Classification by Processing Method

Sun-dried fruits include raisins, dates, and Mediterranean apricots, processed using solar energy with minimal technological intervention. Dehydrated fruits undergo controlled temperature and airflow in commercial facilities, producing consistent results for products like banana chips and mango strips. Freeze-dried fruits utilize sublimation technology, removing moisture while preserving cellular structure and maximizing nutrient retention.

Botanical Categories and Nutritional Highlights

Tree nuts like almonds, walnuts, and cashews provide healthy monounsaturated fats, protein, and vitamin E. Almonds excel in calcium content (264mg per 100g), while walnuts offer plant-based omega-3 fatty acids. Dried vine fruits including raisins and currants concentrate potassium, iron, and natural sugars for quick energy release.

Stone fruit derivatives such as dried apricots and peaches retain high beta-carotene levels, supporting eye health and immune function. Tropical dried fruits like dates and figs provide exceptional potassium levels (656mg per 100g in dates) and unique fiber compositions supporting digestive health.

Comparative analysis reveals that while all dry fruits share certain benefits like fiber content and antioxidants, their micronutrient profiles vary significantly. This diversity allows consumers to target specific nutritional needs through strategic selection rather than viewing all dry fruits as nutritionally equivalent.

In What Ways Can Dry Fruits Be a Sustainable Food Choice?

Dry fruits possess inherent characteristics, most notably their long shelf life, that make them a powerful tool in the fight against food waste, a cornerstone of a sustainable food system.

Reducing Food Waste: The Power of Shelf Stability

According to the FAO, approximately one-third of all food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted globally. Fresh fruits, with their high water content, are among the most perishable items. Drying is a preservation technique that extends the life of a harvest from days into many months. This means less spoilage occurs at the farm, during transport, at the retail store, and in the consumer’s home. A handful of raisins represents grapes that did not spoil, making them a highly waste-efficient food.

Nutrient Density and Transport Efficiency

Because dehydration removes up to 95% of the water weight, dry fruits are a concentrated form of nutrients and calories. Dried fruits require less fuel and space to transport than fresh fruits. This improves nutrient transport efficiency, as argued by some agricultural economists. However, a full Lifecycle Assessment (LCA)—a key tool used by sustainability scientists—presents a more complex picture, as the energy used for artificial dehydration can sometimes offset these transport savings.

Potential for Low-Input Traditional Methods

Traditional sun-drying, when practiced in ideal climates, is a very low-input preservation method. It relies on renewable solar energy and requires minimal technology, representing a historically sustainable practice that is still in use today for products like raisins and some apricots. Natural drying methods demonstrate how traditional knowledge can align with modern sustainability goals.

What are the Major Sustainability Challenges in Dry Fruit Production?

Despite their benefits in reducing waste, the production of many popular dry fruits and nuts faces significant environmental challenges, primarily related to water intensity, energy consumption, and the impacts of large-scale monoculture.

The Challenge of Water Intensity

This is the most well-known issue. The cultivation of certain nut crops is highly water-intensive. Almonds, predominantly grown in the arid climate of California, are the most cited example. It takes approximately 1.1 gallons of water to produce a single almond, according to the Almond Board of California. This places immense strain on local water resources, particularly during drought periods. While the industry is adopting more efficient micro-irrigation systems, water remains a primary sustainability concern.

Energy Consumption in Processing

Most commercial dry fruits are processed with artificial methods, unlike low-energy sun-drying. A food engineer would explain that industrial tunnel dryers, roasters, and processing plants consume substantial amounts of electricity or natural gas. The overall carbon footprint of a dry fruit is therefore heavily influenced by the energy source used in its processing. Studies show that artificial drying can increase the carbon footprint of dried fruits by 200-400% compared to natural drying methods. Additionally, pre-treatment processes like sulfuring, blanching, and osmotic dehydration add further energy requirements while influencing final product quality and shelf life.

Monoculture and Biodiversity Impacts

Large-scale commercial orchards for almonds, walnuts, or pistachios are often vast monocultures (growing only a single crop over a large area). An agricultural economist can explain that this is highly efficient from a production standpoint, but it can have negative environmental consequences, including reduced biodiversity, increased vulnerability to pests, and potential degradation of soil health over time. This model contrasts sharply with traditional agroecological systems, where multiple crops are grown together, fostering greater natural pest control and soil resilience.

Global Production and Consumption Trends

The global dry fruit industry represents a $8.5 billion market with production concentrated in specific geographic regions that possess optimal climate conditions. Understanding these patterns reveals both opportunities and vulnerabilities in the supply chain.

Turkey dominates global production of dried apricots and figs, accounting for 65% and 53% of world production respectively. Iran leads pistachio production with 45% global share, while the United States, primarily California, produces 82% of the world’s almonds. This geographic concentration creates supply chain risks but also enables specialized expertise and infrastructure development.

Consumer trends show dramatic growth in plant-based diets, premium gifting markets, and health-conscious snacking. The global dry fruits market is projected to grow at 6.1% CAGR through 2028, driven by increasing awareness of nutritional benefits and convenience factors. However, this growth must be balanced against price volatility and environmental constraints.

Sustainability and Ethical Considerations in Sourcing

In response to production challenges, a movement towards more sustainable and ethical sourcing practices has emerged, often identifiable through on-package certifications and brand transparency.

A representative from a sustainable food NGO would encourage consumers to look for these key indicators:

- Organic Certification (e.g., USDA Organic): This is a primary indicator of environmental sustainability. Organic farming prohibits the use of most synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, promotes soil health, and helps protect biodiversity.

- Fair Trade Certification: This addresses the social sustainability pillar. A Fair Trade seal ensures that farmers and workers in the supply chain received fair wages and work in safe conditions. It is particularly relevant for imported products where labor practices may be less visible.

- Water-Wise Initiatives: Some brands, particularly in the almond industry, are now transparent about their water management practices, highlighting their use of efficient irrigation to appeal to conscious consumers.

- Support for Biodiversity: Some producers may promote their use of agroforestry or intercropping to show a commitment to moving beyond simple monoculture.

Labor conditions in developing countries present additional ethical considerations. Seasonal workers in Turkish apricot fields and Iranian pistachio groves often face challenging working conditions and low wages. Supporting Fair Trade certified products helps ensure better labor standards and community development investments.

Regenerative and Agroecological Farming Models

Forward-thinking producers are implementing regenerative agriculture and agroforestry systems that go beyond sustainable practices to actively restore ecosystem health. These innovative approaches represent the future of environmentally responsible dry fruit production.

Agroforestry systems integrate tree crops with ground-level vegetation, creating multi-layered ecosystems that support biodiversity while producing food. California almond growers are experimenting with cover crops and beneficial insect habitats, reducing pesticide dependence while improving soil health. Mediterranean fig and olive integrated systems demonstrate how traditional polyculture methods can scale to commercial production.

Regenerative farming practices focus on carbon sequestration, soil restoration, and water cycle improvement. Some pistachio orchards in Iran are adopting rotational grazing with sheep, which provides natural fertilization while maintaining ground cover. These systems often show improved resilience to climate variations while reducing external input requirements.

Permaculture principles applied to nut and fruit tree systems create self-sustaining ecosystems that require minimal external inputs once established. These approaches challenge the conventional monoculture model by demonstrating that productivity and environmental stewardship can coexist profitably.

Dry Fruits vs. Other Protein Sources: Sustainability Comparison

When evaluated against animal proteins and legumes, dry fruits occupy a middle ground in sustainability metrics, offering unique advantages in specific contexts.

Water footprint analysis reveals that while almonds require significant water (1,900 liters per kg), they use considerably less than beef (15,400 liters per kg) or cheese (3,200 liters per kg). However, they exceed legumes like lentils (500 liters per kg) and chickpeas (400 liters per kg).

Carbon footprint comparisons show dried fruits generating 1-3 kg CO2 equivalent per kg, compared to beef’s 27 kg CO2 equivalent. Plant-based proteins, including dry fruits and nuts, consistently demonstrate lower environmental impact than animal proteins while providing essential amino acids, healthy fats, and micronutrients.

Dry fruits are especially valuable in food security contexts due to their shelf stability and nutrient density, which reduce reliance on refrigeration.

| Food | Water Footprint (L/kg) | Carbon Footprint (kg CO₂e/kg) | Key Nutritional Angle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Almonds (nuts) | ~1,900 | ~1–3 | Vitamin E, MUFA, protein |

| Raisins (dried fruit) | ~1,600–1,800 | ~1–2 | Iron, potassium, fiber |

| Lentils (legume) | ~400–600 | ~0.9 | Protein, fiber |

| Beef (ruminant) | ~15,000+ | ~27 | Complete protein |

| Cheese (dairy) | ~3,200 | ~9–13 | Protein, calcium |

Preservation Methods and Shelf Life Optimization

Understanding proper preservation and storage techniques maximizes the sustainability benefits of dry fruits by preventing waste and maintaining nutritional quality.

Properly stored dry fruits maintain quality for 6-12 months at room temperature, with some varieties like dates lasting up to 2 years. Key preservation factors include moisture control (maintaining 10-20% moisture content), temperature stability, and protection from light and oxygen exposure.

Home preservation techniques include vacuum sealing, freezer storage for extended periods, and proper container selection. Glass jars with tight-fitting lids, mylar bags with oxygen absorbers, and food-grade buckets provide effective storage solutions. Understanding these methods helps consumers maximize their investment while minimizing food waste.

Commercial preservation innovations include modified atmosphere packaging, which extends shelf life by replacing oxygen with nitrogen or carbon dioxide. These advances support supply chain efficiency while maintaining product quality across global distribution networks.

| Type | Container | Ambient (20–22°C) | Refrigerated | Freezer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun-dried fruits (raisins, dates) | Airtight jar/mylar + O₂ absorber | 6–12 months | 12–18 months | 18–24 months |

| Nuts (almonds, walnuts) | Vacuum bag/airtight tin | 3–6 months | 6–12 months | 12–24 months |

| Freeze-dried fruits | Mylar + O₂ absorber | 12–24 months | 24–36 months | Up to 5 years |

Innovative Uses of Dry Fruits Beyond Traditional Snacking

Modern applications of dry fruits extend far beyond simple snacking, encompassing culinary innovations, natural sweeteners, and even non-food applications that maximize resource utilization.

Culinary innovations include date paste as natural sugar replacement in baking, reducing refined sugar consumption. Nut flours from almonds and cashews provide gluten-free alternatives for health-conscious consumers. Dried fruit powders serve as natural flavor enhancers and nutritional supplements.

Food industry applications utilize dried fruits in energy bars, breakfast cereals, and functional foods. The natural preservation properties and concentrated flavors make them valuable ingredients for manufacturers seeking clean-label products.

Non-food uses—such as using almond shells for biomass fuel or walnut shells as abrasives—illustrate how dry fruit byproducts can be fully utilized. Almond shells become biomass fuel and livestock bedding. Walnut shells serve as abrasive media in industrial cleaning. Date pits can be processed into activated charcoal for water filtration systems, exemplifying circular economy principles.

What is the Consumer’s Role in Promoting a Sustainable Dry Fruit Industry?

Consumers hold significant power to drive the dry fruit industry towards greater sustainability through their purchasing decisions and consumption habits. Your choices send a direct market signal to producers and retailers.

Here are key actions consumers can take:

- Vote with Your Dollar: When you choose to buy products with Organic or Fair Trade certifications, you create economic demand for those better practices.

- Embrace Variety: Instead of relying only on the most resource-intensive nuts, explore a wider variety of dry fruits and seeds that may have a smaller environmental footprint.

- Avoid Personal Food Waste: The sustainability benefit of a long shelf life is only realized if the product is actually consumed. Buy only what you need and store it properly to prevent spoilage at home.

- Contact Brands: Ask companies about their water management, labor policies, and packaging. Consumer inquiry can pressure brands to become more transparent and adopt more sustainable practices.

- Support Local When Possible: Choose regionally appropriate dry fruits to reduce transportation impacts while supporting local agricultural economies.

Creating homemade trail mixes and energy snacks allows consumers to control ingredients, reduce packaging waste, and customize nutritional profiles to their specific needs.

Common Myths and Misconceptions About Dry Fruits

Despite their established nutritional benefits, dry fruits are subject to numerous misconceptions that can influence consumer choices and sustainability perceptions.

Myth 1: “Dry Fruits Are Too High in Calories to Be Healthy”

Reality: While dry fruits are calorie-dense, they provide essential nutrients in concentrated form. A 1-ounce serving of almonds (160 calories) delivers protein, healthy fats, vitamin E, and magnesium. The key is appropriate portion sizes, not avoidance.

Myth 2: “All Sugar in Dry Fruits Is Unhealthy”

Reality: Natural sugars in dry fruits come packaged with fiber, antioxidants, and minerals, creating a different metabolic response than refined sugars. The fiber content slows sugar absorption, preventing rapid blood glucose spikes.

Myth 3: “Dried Fruits Are Just as Nutritious as Fresh”

Reality: While many nutrients concentrate during drying, some vitamins (particularly vitamin C) are reduced. However, other compounds like antioxidants may actually increase in bioavailability through the drying process.

Understanding these evidence-based facts helps consumers make informed decisions rather than falling victim to nutritional misinformation.

Frequently Asked Questions on Dry Fruit Sustainability

Which dry fruit is the most sustainable?

The most sustainable dry fruit depends on factors like water use, processing method, and transportation distance. A sun-dried raisin from an organic, local farm could be highly sustainable, while a conventionally grown nut transported across the world has a much larger footprint. Generally, products that require less water and processing are more sustainable.

Is organic dried fruit always more sustainable?

Organic dried fruit is often more sustainable in terms of pesticide and fertilizer use, but it may still have a high water or energy footprint. However, it does not automatically guarantee low water or energy use, so it’s one important piece of a larger puzzle.

Does the packaging of dry fruits impact their sustainability?

Packaging affects sustainability by influencing material use, waste generation, and transport emissions. Look for brands that use recyclable materials or less packaging overall. Bulk buying can be a good option to reduce packaging waste, provided you can store the product properly to avoid spoilage.

How does a “lifecycle assessment” (LCA) for food work?

A lifecycle assessment is a comprehensive scientific method used to evaluate the total environmental impact of a product from “cradle to grave.” This includes raw material extraction, farming, processing, transportation, consumer use, and final disposal.

Are there any “water-wise” nuts?

While all nuts require water, some are less intensive than others. For example, peanuts (which are legumes) and some varieties of hazelnuts generally have a lower water footprint compared to almonds or pistachios, especially when grown in suitable climates.

How do processing methods affect sustainability?

Processing methods significantly impact environmental footprint. Sun-drying uses renewable energy and minimal infrastructure, while industrial dehydration requires substantial electricity or gas consumption. Choosing naturally dried products when available reduces energy demand.

Conclusion: Balancing Benefits and Challenges

The sustainability profile of dry fruits embodies the complexity of modern food systems, where exceptional benefits in waste reduction and nutritional density must be weighed against legitimate environmental concerns. As consumers become increasingly conscious of their food choices, understanding these nuances becomes essential for making informed decisions.

Moving forward, producers, consumers, and policymakers must work together to address water use, energy demands, and labor conditions—while still preserving the benefits of dry fruits. Innovation in processing technologies, adoption of sustainable farming practices, and informed consumer choices can drive the industry toward greater sustainability.

Ultimately, dry fruits represent neither a perfect solution nor a problematic choice, but rather an opportunity to engage with the complexities of sustainable eating. By supporting responsible producers, practicing mindful consumption, and continuing to educate ourselves about food system impacts, we can enjoy the nutritional and practical benefits of dry fruits while working toward a more sustainable future.

How we reviewed this article:

▼This article was reviewed for accuracy and updated to reflect the latest scientific findings. Our content is periodically revised to ensure it remains a reliable, evidence-based resource.

- Current Version 18/08/2025Written By Team DFDEdited By Deepak YadavFact Checked By Himani (Institute for Integrative Nutrition(IIN), NY)Copy Edited By Copy Editors

Our mission is to demystify the complex world of nutritional science. We are dedicated to providing clear, objective, and evidence-based information on dry fruits and healthy living, grounded in rigorous research. We believe that by empowering our readers with trustworthy knowledge, we can help them build healthier, more informed lifestyles.