This guide shows how to identify each species by bark texture, husk splitting patterns, and leaf structure. You’ll learn which nuts taste sweet versus bitter, proper curing techniques, and effective cracking methods for extracting flavorful kernels.

Quick Identification Summary

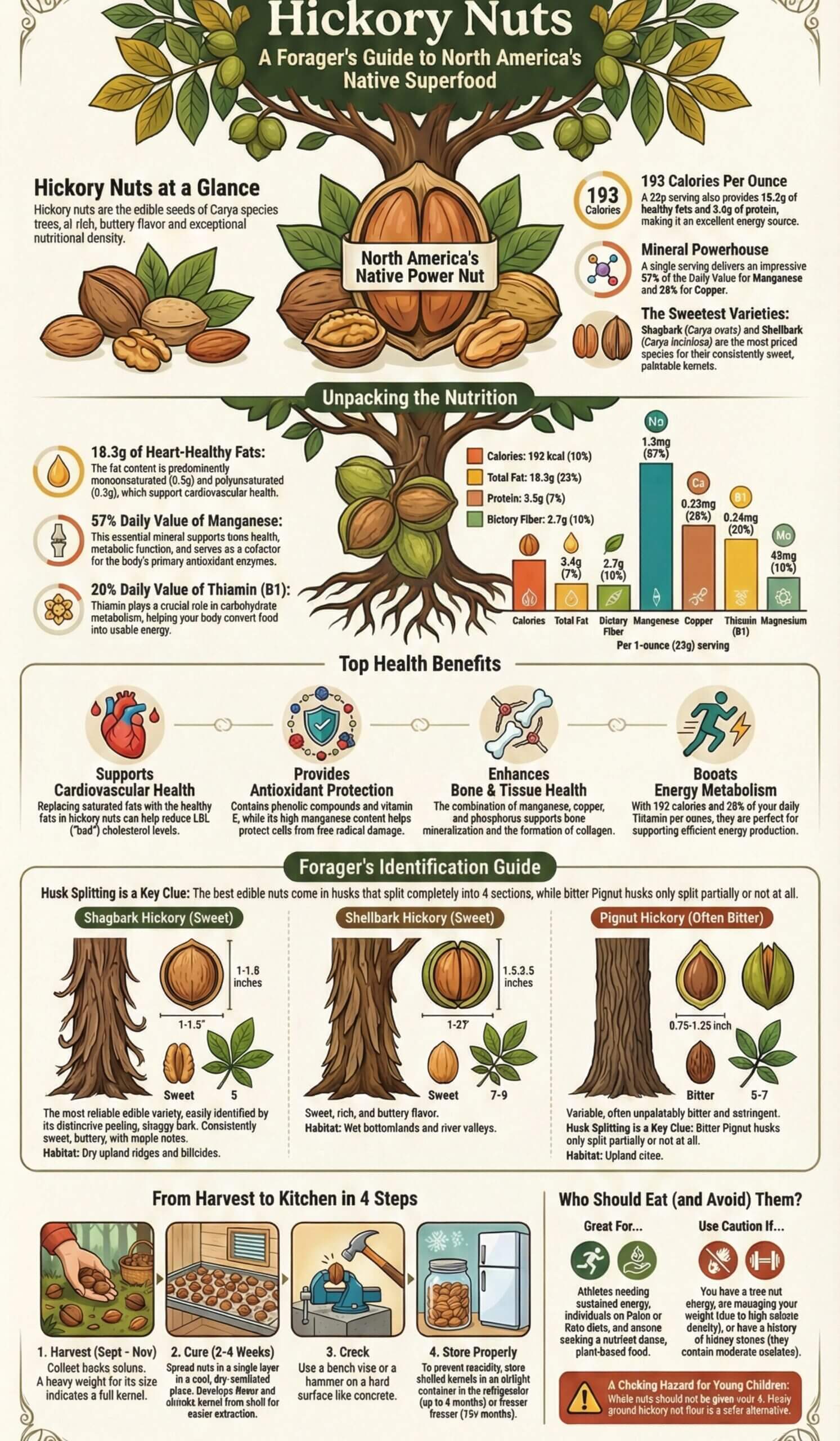

- Shagbark hickory: Shaggy bark strips, 5 leaflets, round nuts with complete 4-section husk split, sweet maple flavor

- Shellbark hickory: Wet bottomland habitat, 7-9 leaflets, largest nuts (2+ inches), very thick shells, sweet taste

- Pignut hickory: Tight bark, 5-7 leaflets, pear-shaped nuts with partial husk split, often bitter from tannins

- Curing requirement: 2-3 weeks drying essential for flavor development and kernel separation from shell

- Harvest timing: Late September through November when husks split and turn brown

What Are Hickory Nuts? How to Identify Carya Species (Quick Traits)

Hickory nuts are the edible seeds of trees in the Carya genus, family Juglandaceae. They grow throughout eastern North America, producing hard-shelled nuts enclosed in thick husks. The complete hickory nut profile covers all species characteristics in detail.

Universal Hickory Identification Features

All hickory species share these characteristics:

- Compound leaves: 5-17 leaflets arranged alternately along a central stem

- Drupe structure: Fleshy outer husk + hard inner shell + kernel (three-layer anatomy)

- Alternate branching: Buds and branches emerge in staggered pattern, not opposite

- Solid pith: Twig centers are solid (unlike walnuts with chambered pith)

- Mast cycles: Heavy nut production every 2-3 years, with lighter crops between

The drupe anatomy distinguishes hickories from true botanical nuts. The husk represents modified flower tissue, while the shell is the actual seed coat. Understanding this structure helps predict how husks split and shells crack.

Hickory vs. Walnut vs. Pecan

Walnuts (Juglans genus): Chambered pith in twigs, husks don’t split cleanly, stronger flavor. Read about walnut origins and taste differences for comparison.

Pecans (Carya illinoinensis): Hickory family member with 9-17 leaflets, thin shells, primarily southern range

True hickories: Fewer leaflets (5-9 typical), very hard shells, broader geographic range. These distinctions matter for accurate identification during foraging.

The term “mast” refers to the nuts and seeds forest trees produce. Hickory mast occurs in boom-and-bust cycles, with heavy production years happening every 2-3 seasons.

How to Identify Shagbark Hickory Nuts (Sweet & Edible)

Shagbark hickory (Carya ovata) produces the sweetest wild nuts in North America. The species name comes from dramatically peeling bark that creates long, vertical strips curling away from the trunk.

Definitive Shagbark ID Markers

Bark (most reliable):

- Long plates (1-3 feet) curl outward at both ends

- Gray to light brown color

- Develops after 20-30 years (young trees have smooth bark)

- Visible from 100+ feet away

Leaves:

- Usually 5 leaflets (occasionally 7)

- Terminal leaflet significantly larger than side leaflets

- Finely serrated edges

- Golden yellow fall color

Nuts (diagnostic):

- Round shape, 1-1.5 inches diameter

- Thick husk splits completely into 4 sections

- Tan to light brown shell

- Medium shell thickness (crackable with effort)

Kernel flavor profile: Sweet, buttery, with maple syrup notes. No bitterness or astringency. Similar to pecans but with cleaner finish. This natural sweetness makes them ideal for trail mix recipes.

Habitat & Geographic Range

Shagbarks prefer well-drained upland sites —ridge tops, hillsides, and elevated plateaus. They grow in mixed hardwood forests from Maine to Georgia, west to eastern Texas and Minnesota.

Soil preference includes loamy, slightly acidic conditions. Trees reach 60-80 feet tall with narrow, oval crowns. Often found growing alongside oaks, maples, and other hickories.

The upland habitat preference distinguishes Shagbarks from Shellbarks, which require wet bottomlands. This ecological separation provides a reliable ID marker when foraging wild foods historically consumed by indigenous groups.

Shellbark vs. Shagbark Hickory: Identification, Taste & Habitat

Shellbark hickory (Carya laciniosa) produces the largest nuts in the Carya genus—earning it the nickname “Kingnut.” Individual nuts can exceed 2 inches in diameter with exceptionally thick, hard shells.

Shellbark Distinguishing Features

Primary differences from Shagbark:

- Habitat: Wet bottomlands, floodplains, river valleys (NOT upland ridges)

- Leaflets: 7-9 per compound leaf (vs. Shagbark’s typical 5)

- Nut size: 1.5-2.5 inches (significantly larger than Shagbark)

- Shell thickness: Extremely thick and hard (requires heavy-duty tools)

The habitat distinction is critical. If you find a shaggy-barked hickory on a dry ridge, it’s a Shagbark. Find one in wet soil near water, and you’ve likely discovered a Shellbark.

Bark Comparison

Both species develop exfoliating bark, but subtle differences exist. Shellbark plates tend wider and less tightly curled, while Shagbark shows narrower plates with more dramatic curves.

These distinctions are subtle. Habitat and leaflet count provide more reliable identification markers. Understanding botanical classification characteristics helps distinguish similar species.

| Feature | Shagbark (C. ovata) | Shellbark (C. laciniosa) |

|---|---|---|

| Nut Size | 1-1.5 inches | 1.5-2.5 inches |

| Leaflets per Leaf | 5 (sometimes 7) | 7-9 |

| Preferred Habitat | Upland ridges, dry sites | Wet bottomlands, floodplains |

| Shell Thickness | Medium-thick | Very thick (hardest to crack) |

| Husk Behavior | Complete 4-way split | Complete 4-way split |

| Kernel Taste | Sweet, maple notes | Sweet, rich, buttery |

| Geographic Range | Widespread eastern US | More limited, river valleys |

Flavor & Kernel Quality

Both Shagbark and Shellbark kernels taste sweet and buttery. No bitterness exists in properly mature nuts from either species.

Flavor notes: Clean nut taste without the tannin astringency of walnuts. Subtle sweetness similar to pecans. Some foragers detect maple undertones in Shagbarks. The macronutrient composition contributes to their rich taste.

The larger Shellbark kernels provide more meat per nut, but the extremely thick shells require heavy-duty cracking tools. This trade-off between yield and processing difficulty influences which species foragers prefer.

Are Pignut Hickory Nuts Edible or Bitter?

Pignut hickory nuts (Carya glabra) are non-toxic but often unpalatably bitter. The species produces variable kernel quality—some trees yield acceptable nuts while others generate astringent kernels high in tannins.

Why Pignuts Taste Bitter

Tannin chemistry: Pignuts contain high concentrations of condensed tannins (proanthocyanidins). These polyphenolic compounds bind to salivary proteins, creating the dry, puckering sensation we perceive as bitterness.

Tannin levels vary based on individual tree genetics, growing conditions, nut maturity, and seasonal weather patterns. This chemical defense mechanism protects nuts from predation but makes many Pignuts unpleasant for humans.

Pignut Physical Identification

Bark (diagnostic):

- Tight, non-exfoliating texture

- Interlocking diamond or narrow ridge pattern

- Smooth compared to Shagbark/Shellbark

- Gray to dark gray color

Nut characteristics:

- Pear-shaped (obovoid) form—wider at top

- 0.75-1.25 inches typical size

- Thin husks that split only partially or stay closed

- Husk splits halfway down at most (not complete 4-way split)

Leaves:

- 5-7 leaflets per compound leaf

- Narrower, more lance-shaped than Shagbark leaflets

- Yellow to golden-brown fall color

The partial husk split provides the most reliable field marker. Shagbark and Shellbark husks split completely into four clean sections. Understanding these botanical terminology differences aids accurate identification.

Testing Pignut Palatability

Never process large batches without taste-testing first. Crack 2-3 nuts from each tree and sample the raw kernel. Bitterness appears immediately—no ambiguity exists.

Process for testing:

- Crack one nut from the tree

- Extract a small piece of kernel

- Chew briefly (5-10 seconds)

- Assess for bitterness or astringency

If bitterness is present, it won’t disappear with roasting or processing. The tannins remain stable at cooking temperatures. This differs from natural sugars in dried fruits that concentrate during processing.

| Feature | Pignut (C. glabra) | Shagbark (C. ovata) |

|---|---|---|

| Bark Texture | Tight, interlocking ridges | Long, shaggy exfoliating plates |

| Nut Shape | Pear-shaped (obovoid) | Round |

| Husk Split Pattern | Partial (halfway) or closed | Complete 4-section split |

| Kernel Taste | Variable—often bitter | Consistently sweet |

| Tannin Content | High (defensive compounds) | Low (palatable) |

Historical Context

Historical records indicate farmers fed these nuts to pigs, who tolerated the bitterness better than humans. The common name reflects agricultural use rather than botanical classification, similar to how ancient civilizations classified food crops.

The scientific name Carya glabra references “glabrous” (smooth) characteristics—the tight bark and relatively smooth twigs compared to shaggy-barked species.

Other North American Hickory Species

Beyond the primary three species, several other hickories grow in eastern forests. Understanding these prevents confusion during identification.

Bitternut Hickory (Carya cordiformis)

Always bitter—never worth harvesting. Bright sulfur-yellow winter buds provide instant identification year-round. Small, thin-husked nuts with heart-shaped cross-section.

The yellow buds are diagnostic—no other hickory displays this trait. If you see yellow buds, skip the tree entirely regardless of nut appearance.

Mockernut Hickory (Carya tomentosa)

Edible but low yield. Very thick shells surrounding small kernels create poor meat-to-shell ratios. The name “mock nut” reflects this disappointing characteristic. Compare to chestnut processing which offers better kernel-to-shell ratios.

Identification markers: Large, hairy leaflets (tomentose = fuzzy), thick husks splitting completely, acceptable but mild flavor. Found on dry upland sites similar to Shagbark habitat.

Red Hickory (Carya ovalis)

Sweet nuts similar to Shagbark. Less common than other species but worth identifying. Sometimes called “sweet pignut” or “false shagbark.”

Features: Tight bark (not shaggy), sweet kernels, thin husks splitting completely. The combination of non-exfoliating bark with sweet taste distinguishes it from bitter Pignuts.

Pecan (Carya illinoinensis)

Wild pecans grow in southern bottomlands. Technically a hickory species but cultivated varieties dominate commercial production.

Identification: 9-17 leaflets per leaf (more than any other hickory), thin husks splitting into 4 sections, oblong nuts with pointed ends. Wild specimens have smaller nuts and thicker shells than commercial pecans.

How to Crack and Extract Hickory Nut Kernels (Tools & Tips)

Hickory shells rank among nature’s hardest materials—harder than walnut shells and far harder than almonds or pecans. Success requires proper curing, appropriate tools, and correct technique.

Step 1: Curing Chemistry & Process

Why curing is essential: Fresh nuts contain 15-20% kernel moisture. During curing, this drops to 5-8%, causing the kernel to shrink and separate from the shell interior.

Simultaneously, enzymatic processes convert starches to sugars, developing the characteristic sweet flavor. This transformation mirrors the principles explained in fruit dehydration processes.

Curing protocol:

- Remove husks if still attached (Shagbark/Shellbark husks usually fall away; Pignut husks need prying)

- Spread nuts in single layer on newspaper, cardboard, or mesh screens

- Choose well-ventilated location: garage, basement, covered porch

- Avoid direct sunlight (causes uneven drying and rancidity)

- Maintain 60-70°F temperature with low humidity

- Cure for 2-3 weeks minimum (4 weeks optimal)

Quality check during curing: Inspect weekly for mold (gray/black fuzz) or weevil exit holes (small round openings). Discard damaged nuts immediately using similar food quality assessment techniques.

The float test identifies bad nuts: Fill container with water, drop in nuts. Good nuts sink; damaged, empty, or moldy nuts float. This works because damaged kernels lose density.

Step 2: Cracking Tool Selection

Tool effectiveness ranking:

1. Bench vise (most control):

- Provides slow, controlled pressure

- Produces clean breaks with minimal shell fragmentation

- Align nut sutures with vise jaws for best results

- Tighten gradually until crack sound occurs

2. Hammer method (most accessible):

- Place nut on concrete, flat stone, or metal anvil

- Use standard 16-oz claw hammer

- Strike with moderate force—don’t pulverize

- Aim for suture lines where shell naturally splits

- Wear safety glasses (shell fragments fly)

3. Heavy-duty lever crackers:

- Tools designed for black walnuts work adequately

- Examples: “Grandpa’s Goody Getter,” commercial nutcracker models

- Standard kitchen nutcrackers will break—don’t attempt

- Provides consistent results once technique is mastered

The mechanical advantage of vises and lever crackers concentrates force efficiently. Hammer methods rely on impact shock waves. Both work when applied correctly to cured nuts. Understanding proper home processing techniques prevents common mistakes.

Step 3: Kernel Extraction Technique

Post-crack process:

- Use nut pick (thin metal hook) or narrow-blade knife

- Insert into shell cracks and pry gently

- Properly cured kernels release in large sections

- Stubborn kernels indicate insufficient curing—recure remaining nuts

Work in well-lit area on clean surface. Light-colored background (white plate or cutting board) makes shell fragments visible so you can avoid eating them.

Step 4: Storage & Shelf Life

High fat content requires careful storage:

- Refrigerated (airtight container): 3-4 months before rancidity develops

- Frozen (freezer bags): 12+ months with minimal quality loss

- Room temperature: 2-3 weeks maximum (oleic acid oxidizes rapidly)

Rancidity indicators: Paint-like or chemical odor, bitter taste (different from tannin bitterness), yellowish discoloration. The unsaturated fatty acids oxidize when exposed to heat, light, or oxygen—similar patterns affect all high-fat nuts and seeds.

Unshelled nuts store for years in cool, dry conditions. Many foragers crack small batches as needed rather than processing entire harvests at once.

Are Hickory Nuts Healthy? Nutrition, Fats & Minerals

Hickory nuts provide exceptional caloric density with beneficial fatty acid profiles. A 1-ounce (28g) serving contains approximately 186 calories, 18g fat, 3.6g protein, and 5.2g carbohydrates.

Fatty Acid Composition & Heart Health

Lipid profile breakdown:

- Monounsaturated fats (MUFA): 9.5g per ounce (53% of total fat)

- Polyunsaturated fats (PUFA): 6.2g per ounce (34% of total fat)

- Saturated fats: 2.3g per ounce (13% of total fat)

The dominant fatty acid is oleic acid (C18:1), a monounsaturated omega-9 fat. This same compound provides the cardiovascular benefits associated with olive oil and almonds. Learn more about healthy fat profiles in tree nuts.

Research links oleic acid consumption to reduced LDL cholesterol oxidation, improved endothelial function, decreased inflammation markers, and enhanced insulin sensitivity.

Micronutrient Density

Significant mineral content per 1-ounce serving:

- Magnesium: 43mg (11% DV) — essential for energy metabolism and muscle function

- Manganese: 1.3mg (57% DV) — antioxidant enzyme cofactor

- Phosphorus: 82mg (7% DV) — bone health and ATP production

- Copper: 0.4mg (44% DV) — iron absorption and connective tissue formation

- Zinc: 1.1mg (10% DV) — immune function support

B-vitamin content:

- Thiamine (B1): 0.2mg (17% DV) — carbohydrate metabolism

- Folate: 15mcg (4% DV) — DNA synthesis

- Pyridoxine (B6): 0.15mg (9% DV) — neurotransmitter production

The high manganese content is particularly notable—hickories provide more per ounce than most cultivated tree nuts. Explore detailed micronutrient profiles for comparison.

Comparative Nutrition Analysis

| Nutrient | Hickory | Pecan | Walnut | Almond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calories | 186 | 196 | 185 | 164 |

| Total Fat (g) | 18 | 20 | 18.5 | 14 |

| Protein (g) | 3.6 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 6 |

| Net Carbs (g) | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2 | 3 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 43 | 34 | 45 | 76 |

Diet Compatibility

Ketogenic diets: The 2.4g net carbs per ounce makes hickories excellent for keto. Use the net carb calculator to track daily intake and compare to macadamias (1.5g) and pecans (1.2g).

Paleo diets: As an ancestral wild food consumed for 10,000+ years, hickories perfectly align with paleo principles. Archaeological evidence from sites across eastern North America shows consistent hickory nut utilization. Review the complete paleo-approved nut guide for context.

Whole30, grain-free, vegan: Hickories meet requirements for all these dietary approaches. The complete amino acid profile provides plant-based protein, though not as concentrated as high-protein nuts like almonds.

Historical Native American Uses

Hickory milk (pawcohiccora/kanuchi): Indigenous groups pounded kernels with water to create nutritious milk. This technique extracted fat-soluble nutrients and created portable, storable nutrition.

The Algonquin term “pawcohiccora” gave us the English word “hickory.” The milk could be drunk fresh as beverage, stored in bark containers for weeks, thickened into cream for cooking, or mixed with corn or roots for complete meals.

Archaeological analysis of middens (ancient trash heaps) reveals hickory shells in massive quantities—sometimes thousands of pounds per site. This indicates hickories served as staple calories, not occasional snacks.

When and How to Harvest Wild Hickory Nuts

Timing determines harvest success more than any other factor. Too early yields immature kernels. Too late means squirrels claim the entire crop.

Optimal Harvest Window by Region

- Northern range (Maine to Minnesota): Late September through October

- Mid-Atlantic (Pennsylvania to Virginia): Early October through early November

- Southern range (Georgia to Texas): Mid-September through mid-October

Maturity indicators: Husks transition from green to brown, husk splits begin opening (Shagbark/Shellbark), first fallen nuts appear under trees, and squirrel activity intensifies around trees.

Begin daily ground checks once you observe brown husks. Mature nuts fall readily with gentle tree shaking or wind.

Collection Methods

Ground collection (primary method):

- Walk tree perimeter daily during harvest window

- Collect only brown-husked nuts (green = immature)

- Check for weevil exit holes (small round openings)

- Avoid moldy or obviously damaged specimens

Tarp method (for accessible trees):

- Spread large tarp under productive tree

- Shake lower branches gently (requires permission on private land)

- Collect ripe nuts that fall

- Leave tarp for repeat collections every 2-3 days

The tarp technique works best for Shagbark and Shellbark where husks split completely. Pignut husks often stay partially closed, making them harder to shake loose.

Quality Assessment in the Field

Visual inspection checklist:

Accept: Completely brown husks (or husk-free nuts with clean shells), heavy weight for size (indicates full kernel), no visible holes or cracks, fresh appearance (not weathered or gray)

Reject: Green husks (immature kernels), small holes (weevil damage—larvae ate kernel), mold (fuzzy gray/black growth), abnormally light weight (empty or damaged), cracked shells (allows moisture and mold entry)

Weevil biology: Hickory nut weevils (Conotrachelus species) lay eggs in developing nuts during summer. Larvae tunnel through kernel, consuming it before boring exit hole in fall. The 1/16-inch hole indicates the adult already emerged, leaving an empty or partially eaten kernel.

Wildlife Competition Strategies

Squirrels, deer, turkeys, and wild hogs all harvest hickories aggressively. Competition is fierce in areas with healthy wildlife populations.

Tactics for beating wildlife: Scout productive trees in summer (mark with GPS), begin collection the instant first nuts drop, check trees daily during peak drop (squirrels work fast), focus on less-accessible locations (steep slopes, dense understory), and collect early morning before wildlife activity peaks.

Squirrels can strip a tree in 3-5 days once harvesting begins. Speed matters more than thoroughness during peak drop periods.

How to Use Hickory Nuts in Cooking & Recipes

Once you’ve invested time processing hickories, use them in ways that showcase their unique sweet, buttery flavor.

Raw Consumption

Properly cured Shagbark and Shellbark kernels taste excellent eaten raw. The sweet flavor with maple undertones requires no enhancement.

Texture: Firmer and less oily than walnuts, closer to almonds in mouthfeel. The kernels crack cleanly between teeth rather than crushing into paste. Compare textures using the texture profile tool.

Baking & Dessert Applications

Direct substitutions: Replace pecans 1:1 in any recipe. The similar flavor profiles work identically in pecan pie, cookies and brownies, quick breads and muffins, coffee cakes, and biscotti.

The hardness means hickory pieces stay crunchy after baking, unlike softer nuts that can become soggy. This provides excellent texture contrast in breakfast applications. Try them in homemade granola recipes for added crunch.

Traditional Hickory Milk

Traditional Native American preparation:

- Blend 1 cup shelled hickory nuts with 3 cups water

- Process until completely smooth (2-3 minutes on high)

- Strain through cheesecloth or nut milk bag

- Squeeze thoroughly to extract all liquid

- Store refrigerated up to 5 days

The resulting milk has rich, nutty sweetness without added sugar. Use anywhere you’d use almond milk—coffee, smoothies, cereal, baking. Enhance with additions from the smoothie booster calculator.

Unlike commercial nut milks with gums and stabilizers, hickory milk contains only nuts and water. This means higher calorie density and authentic flavor.

The Roasting Technique

Roasting protocol for deeper flavor:

- Spread shelled kernels on baking sheet (single layer)

- Roast at 350°F for 8-10 minutes

- Stir halfway through for even browning

- Watch carefully—burned nuts taste acrid

- Cool completely before storing

Roasting develops the Maillard reaction, creating hundreds of flavor compounds. The maple notes intensify and toasted caramel flavors emerge.

Seasoning options: Salt while warm for savory snack, maple syrup + cinnamon for sweet coating, or smoked paprika + garlic powder for umami notes.

Savory Applications

Hickories work in savory contexts as well as sweet. Add crunch and richness to salads similar to pecans, fold into wild rice or quinoa pilaf, toast and sprinkle over roasted Brussels sprouts or green beans, or substitute for pine nuts in basil pesto.

Create custom combinations with the flavor pairing generator to discover complementary ingredients.

Frequently Asked Questions About Hickory Nuts

Q: Are hickory nuts edible?

Yes—some species are sweet and edible (Shagbark, Shellbark), while others (Pignut, Bitternut) are technically edible but often bitter. All hickories are non-toxic, but palatability varies dramatically by species due to tannin content.

Q: How to identify edible hickory nuts?

Look for shaggy bark, complete 4-way husk split, and round nut shape. Shagbark and Shellbark provide these markers. Sweet aroma and medium shell thickness confirm edible species.

Q: What does a shagbark hickory nut look like?

Round nuts (1-1.5 inches) with thick green husks that split into four sections, revealing tan shells underneath. The distinctive shaggy bark makes tree identification easy year-round.

Q: Can you eat pignut hickory nuts?

Pignut kernels are safe but often too bitter to enjoy. High tannin levels create astringency. Test individual trees by cracking 1-2 nuts first—bitterness is immediately obvious.

Q: What is the easiest way to crack hickory nuts?

Hammer on concrete offers most control. Place cured nut on solid surface, strike at suture lines with moderate force. Creates clean cracks without pulverizing kernel.

Q: Do you have to dry hickory nuts before cracking?

Yes—2-3 weeks curing is essential. Drying shrinks kernel away from shell, develops sweet flavor, and enables clean extraction. Fresh nuts stick to shells and taste astringent.

Q: Are hickory nuts good for you?

Hickories provide healthy fats, protein, and minerals. High in oleic acid (heart-healthy MUFA), magnesium, manganese. 186 calories per ounce with beneficial fatty acid profile.

Q: Why are pignut hickories bitter?

High tannin levels create astringency. These polyphenolic compounds defend against pests. Concentration varies by individual tree genetics and growing conditions.

Q: How much are hickory nuts worth?

Shelled kernels sell for $15-30 per pound when available. Rarely appear in commercial markets due to difficult processing. Most consumption comes from personal foraging.

Q: When do hickory nuts fall?

Late September through November depending on location. Southern populations ripen earlier. Watch for brown husks and first ground drops as timing signals.

Q: Difference between shagbark and shellbark hickory?

Habitat and leaflet count differ most. Shagbarks grow on dry ridges with 5 leaflets. Shellbarks inhabit wet bottomlands with 7-9 leaflets. Shellbark nuts are notably larger (2+ inches).

Q: Can you eat hickory nuts raw?

Yes—cured Shagbark and Shellbark nuts taste excellent raw. Sweet, buttery flavor needs no preparation. Always cure 2-3 weeks first; fresh nuts taste astringent.

Q: What tree has hickory nuts?

Trees in the Carya genus produce hickory nuts. About 12 species grow in North America. Most common are Shagbark, Pignut, Mockernut, and Bitternut.

Q: Are all hickory nuts edible?

All are non-toxic but not all taste good. Shagbark and Shellbark are sweet. Pignut and Bitternut often taste too bitter despite being safe to eat. Review common nut myths for more clarification.

Q: Is shagbark hickory good to eat?

Yes—Shagbark produces the sweetest wild nuts in North America. Rich, buttery kernels with maple undertones. Considered superior to many cultivated nuts in flavor complexity.

Q: Are shellbark hickory nuts edible?

Yes—Shellbarks are highly edible with sweet, rich flavor. Larger than Shagbarks but with thicker shells requiring heavy-duty cracking tools.

Master Hickory Nut Identification for Successful Foraging

Species identification separates satisfying foraging experiences from wasted effort. Shagbark and Shellbark hickories reward patient foragers with exceptional sweet nuts—some of the finest wild foods in eastern North America.

The key markers are straightforward once you know what to observe: shaggy bark indicates sweet nuts, tight bark suggests bitterness. Complete husk splits mean easy harvest, partial splits signal lower quality. Upland habitat versus wet bottomland distinguishes Shagbark from Shellbark.

Pignut hickories teach the important lesson that “edible” doesn’t equal “palatable.” The tannin chemistry creating their bitterness won’t disappear with processing. Sample before committing to large-scale harvest—a principle that applies across all dried and preserved foods.

The curing period is non-negotiable. Those 2-3 weeks transform tough, astringent kernels into sweet, easily extracted meat. Patience produces results worth the wait.

With proper identification skills, appropriate tools, and realistic expectations, you can join millennia of humans who’ve recognized hickory nuts as true forest treasure.

How we reviewed this article:

▼This article was reviewed for accuracy and updated to reflect the latest scientific findings. Our content is periodically revised to ensure it remains a reliable, evidence-based resource.

- Current Version 13/01/2026Written By Team DFDEdited By Deepak YadavFact Checked By Himani (Institute for Integrative Nutrition(IIN), NY)Copy Edited By Copy Editors

Our mission is to demystify the complex world of nutritional science. We are dedicated to providing clear, objective, and evidence-based information on dry fruits and healthy living, grounded in rigorous research. We believe that by empowering our readers with trustworthy knowledge, we can help them build healthier, more informed lifestyles.