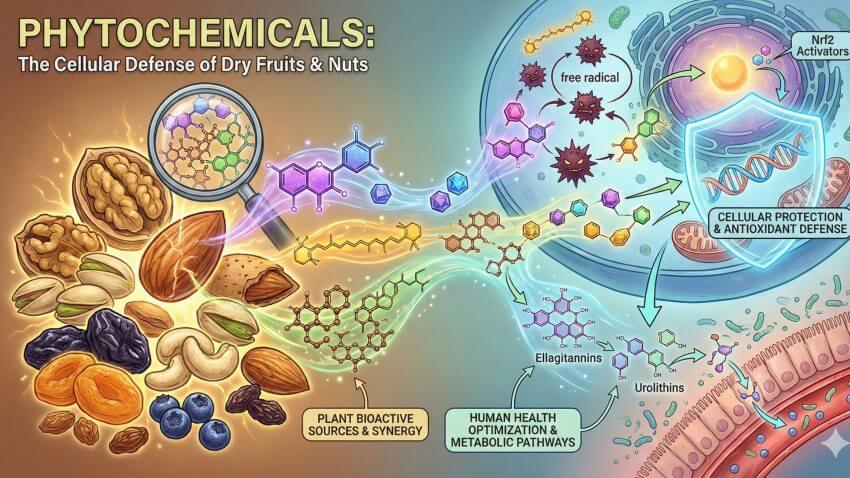

You track macronutrients and count calories. But phytochemicals receive less attention despite their significant role in disease prevention. Phytochemicals are bioactive compounds found in plant-based foods. They are not technically essential for survival. However, they play a pivotal role in modulating human health and protecting against chronic disease.

Key Takeaways

- Phytochemicals are non-essential but biologically active compounds produced by plants that can influence human health. Dry fruits and nuts are exceptionally concentrated sources of these molecules.

- The largest and most studied group are Polyphenols, which includes flavonoids (like anthocyanins in dried berries), phenolic acids, lignans (abundant in flax seeds), and stilbenes (like resveratrol in raisins).

- Other key classes include Carotenoids (like beta-carotene in apricots and lutein/zeaxanthin in pistachios) and Phytosterols (abundant in most nuts and seeds), which help block cholesterol absorption.

- These compounds exert protective effects through multiple mechanisms, including antioxidant activity (neutralizing free radicals), anti-inflammatory effects (modulating cellular signaling pathways like Nrf2), and hormone modulation.

- Bioavailability is Key: The amount of a phytochemical you consume isn’t the same as the amount you absorb. Factors like the food matrix, processing methods, and gut health are critical. The benefits are often a result of synergistic effects between multiple molecules working together.

- The skin matters: Almond skins contain the majority of the nut’s flavonoid content. Blanching removes most of these protective polyphenols.

What Are Phytochemicals and How Do They Differ From Essential Nutrients?

Phytochemicals, or phytonutrients, are chemical compounds produced by plants (“phyto” is Greek for plant) that are not required for normal body function, yet have biological activity and can influence health. A nutritional biochemist would draw a clear distinction between these compounds and the nutrients we typically track.

Essential nutrients—vitamins, minerals, essential amino acids, and essential fatty acids—are required for life. A deficiency will cause a specific disease or dysfunction. Vitamin C deficiency causes scurvy. Iron deficiency causes anemia. These are non-negotiable requirements for human survival.

Phytochemicals are different. A lack of them does not cause a classic deficiency disease, but a diet rich in them is strongly associated with a reduced risk of numerous chronic diseases including cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic syndrome. They represent the difference between mere survival and optimal health.

These compounds often serve as the plant’s own defense system against pests, UV radiation, and other environmental stressors. When we consume the plant, we co-opt these protective benefits. For a deeper look at the overall chemical makeup of these foods, see our article on Macronutrients in Dry Fruits and Nuts and our Complete Guide to Micronutrients.

How Do Phytochemicals Protect Your Body at the Cellular Level?

This section explains the protection mechanisms at the cellular level. The explanation goes beyond generic antioxidant claims.

Phytochemicals work through multiple pathways. These include direct free radical neutralization, gene expression modulation, and inflammatory pathway inhibition.

Direct Antioxidant Activity: Neutralizing Free Radicals

The most well-known mechanism is direct antioxidant activity. Your body constantly produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals as byproducts of normal metabolism.

Some ROS play important signaling roles. Excessive amounts cause oxidative stress. This leads to damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA.

Phytochemicals like flavonoids and phenolic acids act as electron donors. They donate electrons to stabilize free radicals. This prevents these reactive molecules from attacking cellular structures.

Studies measuring ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity) values provide comparative data on in vitro antioxidant capacity. Certain dry fruits rank high in these laboratory assays. However, ORAC values do not reliably predict in vivo antioxidant effects in humans.

The USDA withdrew its ORAC database in 2012, noting that these in vitro measurements do not necessarily translate to health benefits. Our ORAC calculator provides these values for comparative reference, with appropriate caveats.

Indirect Protection: Potential Gene Expression Modulation via the Nrf2 Pathway

In vitro and animal studies suggest many phytochemicals may activate cellular defense systems at the genetic level. This mechanism has been studied primarily in laboratory settings.

The Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) pathway is a master regulator of cellular defense. Laboratory studies show that when activated by compounds like sulforaphane or ellagic acid, Nrf2 translocates to the cell nucleus.

In these studies, it upregulates the expression of over 200 cytoprotective genes. These genes produce antioxidant enzymes including glutathione, superoxide dismutase, and catalase.

Human intervention trials examining these pathways with whole food consumption remain limited. The extent to which dietary phytochemicals from nuts and dried fruits activate these pathways in humans requires further investigation.

Anti-Inflammatory Signaling: Potential Inflammatory Pathway Modulation

Chronic low-grade inflammation underlies most age-related diseases. In vitro and animal studies show phytochemicals may modulate inflammatory pathways by inhibiting key enzymes like COX-2 and lipoxygenase.

Laboratory research suggests suppression of NF-κB (Nuclear factor kappa B) activation, a protein complex that controls inflammatory gene expression. Human clinical trials examining these specific mechanisms with dietary nut and dried fruit consumption remain limited.

When you consume polyphenol-rich walnuts or anthocyanin-rich dried berries, laboratory evidence suggests these compounds may influence gene expression patterns related to inflammatory pathways. Human clinical studies examining these specific mechanisms remain limited. For those managing inflammation, our Joint Pain & Inflammation Nutrients Calculator can help identify potentially beneficial dry fruit combinations.

Hormone Modulation and Cell Signaling

Some phytochemicals, particularly lignans from flax seeds and isoflavones from certain nuts, have weak estrogenic activity. They bind to estrogen receptors and can exert either estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects depending on the hormonal environment. This selective estrogen receptor modulation may explain some of the protective effects observed against hormone-related cancers in epidemiological studies.

The mechanisms are complex and interconnected. These aren’t isolated effects—they work in concert, creating a comprehensive protective network within your cells.

What Are the Major Classes of Polyphenols in Dry Fruits and Nuts?

Polyphenols are a vast and diverse family of phytochemicals characterized by the presence of multiple phenol structural units. They are the most abundant phytochemicals in our diet, and dry fruits are an exceptionally concentrated source. The dehydration process removes water but leaves these valuable compounds intact—and in some cases, even more bioavailable.

Flavonoids: A Diverse and Powerful Subgroup

Flavonoids are the largest group of polyphenols, responsible for much of the vibrant color in fruits and their associated health benefits.

Anthocyanins produce the red, purple, and blue pigments you see in berries. Research suggests they have strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties beneficial for vascular health and cognitive function. Key sources include dried blueberries, cranberries, cherries, and the skins of black raisins. The PREDIMED study found that individuals consuming anthocyanin-rich foods had significantly lower cardiovascular disease risk.

Flavan-3-ols include catechins and proanthocyanidins (also called condensed tannins). They are found in grapes, raisins, apples, and nuts like almonds and pecans. These compounds are researched for their role in supporting cardiovascular health, improving endothelial function, and potentially enhancing cognitive performance. The astringent taste you sometimes notice in nut skins? That’s proanthocyanidins.

Flavonols like quercetin and kaempferol are widespread in the plant kingdom. Dried apples, apricots, and cranberries are good sources. Quercetin is a potent antioxidant that has been studied for its anti-inflammatory, antihistamine, and potential antiviral effects. It’s one of the most researched flavonoids in nutritional science.

Phenolic Acids: The Understudied Protectors

These compounds act as antioxidants and are found widely in plant foods, though they receive less attention than flavonoids. Prunes (dried plums) are particularly rich in phenolic acids like neochlorogenic and chlorogenic acids, which contribute significantly to their exceptionally high antioxidant capacity—among the highest of all commonly consumed foods.

Chlorogenic acid has been studied for its potential role in glucose metabolism and may help moderate blood sugar spikes when consumed with carbohydrate-rich meals. For those monitoring blood sugar, our Glycemic Load Calculator can help you understand how different dry fruits affect glucose levels.

Lignans: Phytoestrogens with Unique Roles

Lignans are a class of polyphenols that can be converted by gut bacteria into enterolignans (enterodiol and enterolactone), which have weak estrogenic activity and may play protective roles in hormone-sensitive tissues.

Flax seeds are by far the richest known dietary source of lignans—containing up to 800 times more than most other plant foods. Sesame seeds also contain a significant amount, along with unique lignans like sesamin and sesamolin that have been studied for their liver-protective and lipid-modulating effects.

A pharmacognosist would note that research into lignans is active, exploring their potential role in cardiovascular health, bone density, and hormone-related wellness. The conversion of plant lignans to enterolignans by gut bacteria underscores the critical importance of a healthy microbiome for unlocking phytochemical benefits.

Stilbenes: The Case of Resveratrol

Resveratrol is arguably the most famous stilbene, found in the skins of grapes. Raisins and sultanas are a dietary source, though concentrations are variable depending on grape variety and growing conditions. It is a potent antioxidant that has been extensively researched for its potential cardioprotective and anti-aging effects in laboratory studies.

The challenge with resveratrol is bioavailability—most of it is rapidly metabolized by the liver. However, human clinical trial results are still developing, and the whole-food matrix of raisins may provide benefits beyond isolated resveratrol supplementation due to synergistic effects with other phytochemicals present.

Which Nuts Contain the Highest Phytochemical Content?

Nuts vary significantly in their phytochemical profiles. The following analysis examines the four nuts with the highest concentrations of protective compounds, comparing their ORAC values and unique phytochemical signatures.

| Nut Type | Primary Phytochemicals | ORAC Value (per 100g)* | Unique Compound | Research Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walnuts | Ellagitannins, Polyphenols | 13,541 μmol TE | Ellagic Acid → Urolithins | Brain, Heart, Gut |

| Almonds (with skin) | Flavonoids, Vitamin E | 4,454 μmol TE | Proanthocyanidins (in skin) | Heart, Skin, Cellular |

| Pistachios | Lutein, Zeaxanthin, Polyphenols | 7,675 μmol TE | Highest Lutein among nuts | Eye, Heart, Metabolic |

| Cashews | Anacardic Acids, Polyphenols | 2,010 μmol TE | Anacardic Acid | Metabolic, Antimicrobial |

What Makes Walnuts High in Polyphenols?

Walnuts consistently rank as having high total polyphenol content among tree nuts. Published values typically range from 1,500 to over 1,700 mg/100g depending on variety, though content varies with cultivar, growing conditions, and analytical methods.

The primary polyphenolic compounds are ellagic acid and its precursors, ellagitannins. Gut bacteria can metabolize these ellagitannins into urolithins, particularly urolithin A.

Preclinical research published in Nature Medicine has shown that urolithin A can stimulate mitophagy in model organisms. Mitophagy is the removal of damaged mitochondria. Whether these effects translate to humans at dietary doses requires further research.

This conversion requires a healthy gut microbiome. Studies suggest only 25-50% of people efficiently produce urolithins based on their gut bacteria composition. Controlled feeding studies show variable postprandial responses to walnut consumption, suggesting bioavailability limitations.

This variability may partly explain differential responses to walnut consumption in population studies. Our comprehensive walnut profile explores these benefits in depth.

Beyond ellagitannins, walnuts contain melatonin (supporting sleep and circadian rhythms), and they’re the only nut with an appreciable amount of plant-based omega-3 fatty acids (alpha-linolenic acid), which work synergistically with polyphenols to reduce inflammation.

Practical recommendation: The PREDIMED study found that consuming 30g of mixed nuts daily (about 7 walnut halves) was associated with a 30% reduction in cardiovascular events. For brain health comparisons, see our article on Almonds vs Walnuts for Brain Health.

Why Is Almond Skin Important for Phytochemical Content?

A substantial proportion of the flavonoid content in almonds resides in the brown skin. Research indicates the skin contains concentrated amounts of proanthocyanidins and other polyphenols. When almonds are blanched to remove the skin, much of their phytochemical content is discarded.

The exact percentage varies by cultivar, extraction method, and analytical technique. Published reviews note wide variation but consistently show the skin as the primary reservoir of flavonoid compounds.

The almond skin is rich in proanthocyanidins (the same compounds that give dark chocolate and red wine their antioxidant reputation), flavonols, and phenolic acids. These compounds work synergistically with the Vitamin E in the almond kernel—which is primarily located in the lipid-rich interior—to provide comprehensive antioxidant protection.

Studies have examined whether polyphenols in almond skins survive digestion and appear in the bloodstream. Some research suggests they may enhance the antioxidant capacity of LDL cholesterol particles in vitro.

Oxidized LDL is a factor in atherosclerosis development. Whether the polyphenol content in dietary almond skins provides clinically meaningful protection against LDL oxidation in vivo requires further investigation.

Observational data from the Adventist Health Study found associations between frequent almond consumption and reduced cardiovascular disease risk. However, isolating the specific contribution of skin polyphenols from other beneficial almond components remains challenging.

Practical recommendation: Always choose almonds with skins intact. If you’re soaking almonds (which can improve digestibility), keep the skins on. Our guide on Soaking Nuts and Seeds explains the proper technique.

What Unique Carotenoids Do Pistachios Contain?

Pistachios have a unique phytochemical profile among nuts. They are the richest source of the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin. These two yellow pigments give pistachios their characteristic green-yellow kernel color.

Your retina constantly faces oxidative stress from light exposure—particularly blue light. Lutein and zeaxanthin accumulate in the macula where they act as both antioxidants and a physical blue light filter, protecting the delicate photoreceptor cells from damage. Epidemiological studies consistently link higher dietary intake of these carotenoids with reduced risk of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and cataracts.

Beyond eye health, pistachios contain a robust polyphenol profile including anthocyanins, flavonols, and proanthocyanidins. Recent research has focused on their potential metabolic benefits—studies show that pistachio consumption can improve glycemic control, reduce oxidative stress in diabetic individuals, and beneficially modify gut microbiota composition.

Interestingly, pistachios have a lower calorie content per serving than most other nuts (about 160 calories per ounce versus 170-200 for others), partly because approximately 10-20% of the fat they contain is not fully absorbed due to the structural characteristics of the nut. This makes them an excellent choice for those watching caloric intake while still wanting phytochemical benefits.

Practical recommendation: A serving of 30g (about 49 pistachios) provides approximately 1.2mg of lutein and zeaxanthin combined. For vision health support, check our Vision Health Nutrient Explorer.

What Unique Compounds Are Found in Cashews?

Cashews contain unique compounds not found in other common nuts. The most notable are anacardic acids, a group of phenolic lipids with demonstrated antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and potential anticancer properties in laboratory studies.

Anacardic acids have shown activity against various bacteria, including Helicobacter pylori (associated with stomach ulcers) and Streptococcus mutans (a primary cause of dental cavities). While most of these compounds are found in higher concentrations in the cashew shell liquid (not the edible nut), the kernel still contains meaningful amounts.

Cashews also provide polyphenols including proanthocyanidins and catechins, though at lower concentrations than almonds or walnuts. Their phytochemical profile works synergistically with their high copper and magnesium content to support metabolic health.

One caveat: cashews are almost always sold roasted because raw cashews contain urushiol (the same irritating compound in poison ivy) in their shell, which is removed during processing. The roasting process can reduce some heat-sensitive phytochemicals, though the major polyphenols remain largely intact. For those following specific diets, our Paleo Diet Guide covers which nuts fit different eating patterns.

Practical recommendation: Choose dry-roasted or lightly roasted cashews over those cooked in oil. A serving of 30g (about 18 cashews) provides metabolic support through both phytochemicals and minerals. Our Macronutrient Calculator can help you track your cashew intake within your daily targets.

How Does Drying Concentrate Phytochemicals in Fruits?

The dehydration process removes water, which concentrates both natural sugars and protective phytochemicals. This creates a unique nutritional profile distinct from fresh fruit.

How Does Water Removal Affect Sugar and Phytochemical Concentration?

When fresh fruit loses water during drying, the weight decreases by 75-90%. The nutrients and phytochemicals do not evaporate. They become concentrated in the remaining mass.

A fresh plum might contain 10mg of polyphenols and 3g of sugar per fruit. When it becomes a prune, those same 10mg of polyphenols remain in a much smaller package that also contains concentrated sugar.

This is why dried fruits are calorie-dense—but it’s also why they’re phytochemical-dense. The key is understanding how the fiber matrix and polyphenol content mitigate the glycemic impact. The same fiber that aids digestion also slows sugar absorption, and polyphenols can inhibit digestive enzymes that break down carbohydrates, further moderating blood sugar spikes.

Studies comparing fresh versus dried fruits show that despite higher sugar content by weight, dried fruits often produce similar or even lower glycemic responses than expected, likely due to these protective mechanisms. Our Fresh vs Dried Fruit Comparison Tool lets you analyze these differences quantitatively.

What Phytochemicals in Prunes Support Bone Health?

Prunes rank high in laboratory antioxidant assays, with in vitro ORAC values exceeding 8,000 μmol TE per 100g. Their primary phytochemicals are phenolic acids, particularly neochlorogenic and chlorogenic acids.

Several clinical trials have examined prune consumption and bone health in postmenopausal women. Some studies using 50-100g daily reported beneficial effects on bone mineral density markers.

Proposed mechanisms involve phenolic compounds potentially influencing osteoclast activity (cells that break down bone) and osteoblast function (cells that build bone). However, the evidence base remains limited, and effects may vary by population, dose, duration, and individual factors.

Reviews caution that while associations exist, causality, optimal dose-response relationships, and long-term efficacy require further investigation.

A 2022 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that women who consumed 50g of prunes daily for one year had significantly higher bone mineral density in the spine and hips compared to the control group. This wasn’t a supplement study—it was whole food intervention demonstrating clinically meaningful results.

Beyond bone health, the high fiber content (both soluble and insoluble) supports digestive health and helps moderate blood sugar despite the natural sugar content. The sorbitol and fiber combination provides gentle laxative effects without the harsh action of stimulant laxatives. For digestive support, see our Guide to Dietary Fiber in Dry Fruits.

Practical recommendation: 5-6 prunes (about 50g) daily provides bone-protective benefits based on clinical trial evidence. If you’re concerned about sugar, consume them with a handful of nuts—the fat and protein further slow sugar absorption.

What Polyphenols Do Dates Contain?

Dates have been cultivated since at least 4000 BCE in Mesopotamia. They can be 60-80% sugar by weight. They also contain a significant polyphenol profile that provides protective benefits.

Dates are rich in flavonoids, particularly flavonols like quercetin. They also contain phenolic acids and carotenoids. These compounds work alongside the fruit’s fiber, potassium, magnesium, and B vitamins.

One unique area of research involves dates and pregnancy. Multiple clinical trials have found that consuming dates during late pregnancy (6 dates daily in the final 4 weeks before due date) is associated with increased cervical dilation, reduced need for labor induction, and shorter first-stage labor. The mechanism isn’t fully understood but may involve compounds in dates that have oxytocin-like effects on uterine tissue.

Different date varieties have different phytochemical profiles. Medjool dates tend to be larger and softer with higher moisture content, while Deglet Noor dates are firmer and slightly less sweet. Darker varieties generally contain higher polyphenol concentrations. For pregnancy nutrition support, explore our Pregnancy Nutrition Calculator.

Practical recommendation: 2-3 dates (about 50g) provide quick energy for pre-workout fuel while delivering polyphenol protection. The natural sugars are absorbed more slowly than refined sugar due to fiber content. For athletic performance, dates work well when combined with nuts for sustained energy.

What Is Oleanolic Acid and Where Is It Found in Raisins?

Raisins contain concentrated sugars. They also contain oleanolic acid, a pentacyclic triterpenoid with demonstrated antibacterial properties against oral bacteria.

Research published in the Journal of Food Science found that phytochemicals in raisins, including oleanolic acid, oleanolic aldehyde, and betulin, inhibit the growth of Streptococcus mutans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. These are two primary culprits in tooth decay and gum disease.

Beyond dental effects, raisins are a concentrated source of resveratrol (found in grape skins), quercetin, catechins, and anthocyanins (in dark raisins). These polyphenols support cardiovascular health through multiple mechanisms: improving endothelial function, reducing LDL oxidation, and modulating blood pressure.

Raisins are also remarkably rich in potassium (about 750mg per 100g) and phenolic acids. The PREDIMED study included raisins as part of the Mediterranean dietary pattern that showed significant cardiovascular benefits. The fiber content (3-4g per 100g) helps moderate the glycemic response despite the concentrated sugar.

Different grape varieties produce different raisins: dark raisins (from red/purple grapes) contain higher anthocyanin levels, golden raisins are often treated with sulfur dioxide to preserve color, and sultanas are typically made from seedless white grapes. For those concerned about sulfites, our guide on Sulphured vs Unsulphured Dry Fruits explains the differences.

Practical recommendation: A small box of raisins (about 30g or 2 tablespoons) provides a portable snack with cardiovascular-supporting polyphenols and quick-digesting energy. They’re particularly useful for athletes as a natural alternative to processed energy gels. Check our Heart Health Calculator to see how raisins fit into your cardiovascular nutrition plan.

What Phytochemicals Are Found in Dried Figs?

Figs have been cultivated since ancient times. Both fresh and dried figs contain flavonoids, anthocyanins, and phenolic acids.

Figs contain hundreds of edible seeds. These seeds contribute fiber, omega fatty acids, and additional phytochemicals. They pass through digestion largely intact, providing insoluble fiber and serving as a prebiotic food source for beneficial gut bacteria.

Figs are particularly rich in benzaldehyde (found in the fruit and leaves), which has been studied for its potential antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. The polyphenol profile includes chlorogenic acid, syringic acid, and catechin, all of which contribute to the fruit’s antioxidant capacity.

Dried figs provide significant amounts of calcium (162mg per 100g), potassium, magnesium, and iron, working synergistically with phytochemicals to support bone and cardiovascular health. The combination of soluble and insoluble fiber (9-10g per 100g) makes them particularly beneficial for digestive health.

Practical recommendation: 3-4 dried figs (about 60g) provide substantial fiber and phytochemicals. Their chewy texture and mild sweetness make them excellent in homemade trail mixes or chopped into salads. For creative uses, see our Homemade Trail Mix Guide.

How Much Beta-Carotene Do Dried Apricots Contain?

Dried apricots are rich in beta-carotene. Published values range from approximately 1,000-2,200 μg per 100g depending on variety, growing conditions, and analytical methods. This makes them one of the richest non-supplement sources of this provitamin A carotenoid.

The bright orange color indicates carotenoid presence. However, exact content varies with cultivar and processing methods.

Many commercial dried apricots are treated with sulfur dioxide to maintain their bright color and prevent browning. This is generally safe for most people. It can trigger asthma symptoms in sensitive individuals.

Dried berries—blueberries, cranberries, cherries—concentrate anthocyanins to remarkable levels. These deep purple and red pigments are among the most powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory phytochemicals studied. Research links anthocyanin intake with improved cognitive function, reduced cardiovascular disease risk, and better glycemic control.

The challenge with dried berries is that many commercial products are sweetened with added sugar to counter their natural tartness. Look for “no sugar added” varieties to maximize the phytochemical-to-sugar ratio. Our Natural vs Added Sugars guide helps you identify truly unsweetened options.

Which Carotenoids Are Prevalent in Dry Fruits and Nuts?

Carotenoids are a class of fat-soluble pigments responsible for the yellow, orange, and red hues in many plants. Some can be converted by the body into Vitamin A, while others provide unique protective benefits independent of vitamin activity.

Beta-carotene is the most well-known provitamin A carotenoid. Dried apricots and dried mangoes are exceptionally rich sources. The body converts beta-carotene to retinol (active Vitamin A), which is essential for vision, immune function, cellular communication, and reproduction. Unlike preformed Vitamin A from animal sources, provitamin A carotenoids carry no risk of toxicity because the body regulates conversion based on needs.

Lutein and zeaxanthin are non-provitamin A carotenoids that concentrate in the macula of the human eye, where they filter blue light and provide antioxidant protection to photoreceptor cells. Among nuts, pistachios are the standout source. Goji berries, when dried, also provide meaningful amounts of these eye-protective compounds.

The fat-soluble nature of carotenoids means absorption depends on the presence of dietary fat in the meal. This is where the synergy of whole foods becomes apparent: when you consume carotenoid-rich dried apricots alongside the healthy fats in almonds or walnuts, you dramatically enhance carotenoid absorption compared to eating the apricots alone. Our Nutrient Absorption Enhancer tool explores these synergistic pairings.

For those interested in skin health, beta-carotene accumulation in skin tissue provides some natural protection against UV damage. While this doesn’t replace sunscreen, it’s a meaningful additional layer of defense. Check our Youthful Skin Nutrient Calculator for comprehensive skin-supporting nutrition plans.

What is the Role of Phytosterols in Nut and Seed Nutrition?

Phytosterols, or plant sterols, are compounds found in plant cell membranes that are structurally very similar to cholesterol in humans. Nuts and seeds are among the richest dietary sources of these molecules. Their similarity to cholesterol is precisely what makes them beneficial.

Mechanism of Action: Competitive Inhibition

A nutritional biochemist would explain their primary benefit through competitive inhibition in the small intestine. Here’s the process: Dietary cholesterol and bile acids (which contain cholesterol) need to be packaged into micelles—tiny transport structures—to be absorbed through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream.

Phytosterols have a near-identical structure to cholesterol, so they compete for the same absorption sites. When phytosterols occupy these sites, dietary cholesterol literally gets crowded out and passes through the digestive system unabsorbed, eventually being excreted. This competition effectively blocks a portion of cholesterol from entering the bloodstream.

Clinical trials have consistently shown that consuming 2-3 grams of phytosterols daily can reduce LDL cholesterol by approximately 8-10%. This effect is additive to statin medications and dietary changes, making phytosterol-rich foods a valuable component of cardiovascular disease prevention strategies.

Key Sources in Nuts and Seeds

Virtually all nuts and seeds provide phytosterols, with beta-sitosterol being the predominant form (typically accounting for 75-90% of total phytosterols). Content varies by variety, growing conditions, and measurement methods.

Reported ranges from published databases include:

- Sesame seeds: High phytosterol content (approximately 400mg per 100g in some analyses)

- Pistachios: Approximately 200-280mg per 100g

- Sunflower seeds: Approximately 270mg per 100g

- Almonds: Approximately 120mg per 100g

- Walnuts: Approximately 110mg per 100g

These values should be considered approximate. Actual content depends on specific variety and processing. Many databases do not quantify all phytosterol classes reliably.

A typical 30g serving of mixed nuts provides 35-60mg of phytosterols—not enough alone to achieve the therapeutic 2g daily target, but meaningful when combined with other phytosterol sources (vegetables, whole grains, legumes) throughout the day.

The presence of phytosterols adds another layer to the cardioprotective profile of nuts and seeds, working alongside their healthy unsaturated fats and polyphenols. This is textbook nutritional synergy—multiple beneficial components working through different mechanisms to achieve comprehensive cardiovascular protection. For lipid health tracking, use our Lipid Profile Impact Estimator.

What Are Terpenoids and Other Emerging Phytochemicals?

Terpenoids (or terpenes) represent a very large and diverse class of plant-produced chemicals. While research is emerging, some found in dry fruits are showing intriguing biological activity. This is a frontier area of nutritional science where preliminary findings are promising but require much more rigorous human investigation.

Ursolic Acid: The Fruit Peel Triterpene

Ursolic acid is a pentacyclic triterpene found in the waxy coating on fruit peels. It’s present in dried apples, prunes, and cranberries, especially when the skins are intact. This compound has garnered attention in sports nutrition and anti-aging research.

Laboratory studies (both in vitro and in animal models) suggest ursolic acid may have several interesting properties. It appears to activate pathways that promote muscle protein synthesis while simultaneously activating brown adipose tissue (metabolically active fat that burns calories). Some studies show it can increase skeletal muscle mass and grip strength in mice, and reduce body fat percentage.

The anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of ursolic acid have also been explored. It appears to modulate several cellular signaling pathways including mTOR, AMPK, and inflammatory cascades, suggesting potential benefits for metabolic health.

However—and this is critical—almost all of this research is in laboratory settings or animal models. Human clinical trials are limited, and bioavailability remains a significant question. An editor of a journal like Phytochemistry would emphasize that while mechanistic studies are intriguing, we cannot yet make definitive claims about human health effects. The amounts in dried fruits are also relatively small compared to doses used in animal studies.

Limonoids: Citrus-Derived Terpenoids

Found in citrus peel, limonoids are present in products like candied or dried lemon and orange zest. These compounds are being investigated for their potential biological activities, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in laboratory studies. Limonin and nomilin are two of the most studied limonoids from citrus.

The challenge with limonoids is similar to ursolic acid: promising preliminary data, but limited human research. They also tend to have a bitter taste, which is why they’re concentrated in the peel and pith rather than the flesh of citrus fruits.

Other Emerging Compounds

Research continues to identify new bioactive compounds in nuts and dried fruits. Betulinic acid (found in birch bark and some nut skins), various tannins, and novel flavonoid derivatives are all areas of active investigation. The sophisticated analytical techniques available today—mass spectrometry, HPLC, metabolomics—allow researchers to identify hundreds of compounds that were previously unknown or unmeasurable.

The takeaway for the informed consumer: emerging research on these compounds is exciting but preliminary. The wisest approach is to consume a variety of whole nuts and dried fruits, trusting that the complex mixture of known and yet-to-be-discovered phytochemicals provides benefits through mechanisms we don’t fully understand yet.

How Do Processing and Storage Affect Phytochemical Content?

The amount and composition of phytochemicals in a final dry fruit product are not static; they are significantly influenced by the fruit’s variety, ripeness at harvest, and the specific processing and storage methods used. Understanding these factors helps you make informed purchasing decisions.

Processing Methods: Heat, Light, and Oxidation

A food scientist would highlight several critical factors in processing. High heat used in some artificial drying methods can degrade heat-sensitive polyphenols and carotenoids. Anthocyanins are particularly vulnerable to heat degradation, which is why gently dried berries retain more of their deep purple color than those subjected to high-temperature commercial drying.

Freeze-drying (lyophilization) generally preserves phytochemicals best because it operates at very low temperatures under vacuum. The fruit’s water sublimates (goes directly from ice to vapor) without passing through a liquid phase, minimizing heat exposure and oxidative damage. This is why freeze-dried berries often have superior color, flavor, and phytochemical retention compared to conventionally dried versions—though they’re also more expensive.

Sun-drying is the traditional method and can preserve phytochemicals reasonably well for less heat-sensitive fruits like raisins, dates, and figs. However, it’s slow, weather-dependent, and carries some risk of contamination. Modern solar dehydrators improve on traditional methods by controlling airflow and providing some protection from environmental contaminants.

Blanching (brief heat treatment) before drying can actually preserve some phytochemicals by inactivating enzymes that would otherwise cause degradation during storage. However, it can also cause some immediate nutrient loss. It’s a trade-off that commercial producers navigate based on the specific fruit. For home drying techniques, see our guides on Using a Food Dehydrator and Oven Dehydration.

Storage Conditions: The Silent Degradation

Once dried, the battle isn’t over. Exposure to light, oxygen, heat, and humidity during storage can lead to progressive degradation of phytochemicals—particularly carotenoids and some polyphenols.

Oxidation is the primary enemy. When phytochemicals act as antioxidants, they sacrifice themselves by becoming oxidized. In storage, this process continues in the presence of oxygen. Vacuum-sealed or nitrogen-flushed packaging dramatically slows this degradation.

Light exposure, particularly UV light, accelerates degradation of many phytochemicals. This is why opaque packaging is superior to clear plastic bags or glass jars for long-term storage. If you buy in bulk and transfer to storage containers at home, choose opaque, airtight containers and store in a cool, dark location.

Temperature control matters significantly. Room temperature (20-25°C) is acceptable for short-term storage, but for nuts and seeds with high fat content, refrigeration or even freezing can significantly extend shelf life and preserve phytochemical content. The oils in nuts can go rancid through oxidation, and this process also affects associated fat-soluble phytochemicals. Our comprehensive Shelf Life Guide provides specific storage recommendations.

Bioaccessibility and Processing Trade-offs

Sometimes processing can actually help nutrient availability. The mechanical grinding of flax seeds, for example, is essential because the hard outer shell is impervious to digestion. Whole flax seeds pass through the digestive tract intact, taking their lignans with them. Ground flax makes the beneficial compounds accessible.

Similarly, roasting nuts can reduce some heat-sensitive vitamins but doesn’t significantly impact their polyphenol content in most cases, and the improved palatability may lead to higher consumption. Light roasting at moderate temperatures (140-160°C) is a reasonable compromise that enhances flavor while preserving most phytochemicals.

The practical takeaway: seek out minimally processed, properly stored products. Look for vacuum-sealed or resealable packaging, opaque containers, and recent production dates. When you open a package, store the contents in airtight containers away from heat and light. For quality assessment, our Food Freshness & Quality Checker can help.

What is Bioavailability and How Does It Affect Phytochemical Absorption?

Bioavailability refers to the proportion of a nutrient or compound in a food that is absorbed and utilized by the body. Understanding this concept is critical, as the amount of a phytochemical you ingest is not always the amount your body gets to use. This is the gap between “eating healthy” and “actually absorbing nutrients.”

The Challenge: Low and Variable Absorption

The bioavailability of phytochemicals is often surprisingly low and highly variable between individuals. Polyphenols, for instance, typically have absorption rates of only 5-10% in their native form. The majority pass through the small intestine unabsorbed and reach the colon, where gut bacteria metabolize them into different compounds—some of which are then absorbed, others excreted.

This isn’t necessarily bad. Those “unabsorbed” polyphenols that reach the colon may exert beneficial effects on the gut microbiome, promoting beneficial bacteria and producing metabolites that influence systemic health. The urolithin production from walnut ellagitannins is a perfect example—it only happens because the parent compounds reach the colon intact.

Factors Influencing Bioavailability

The Food Matrix: A phytochemical’s absorption can be dramatically affected by what else is in your meal. Carotenoids are fat-soluble, meaning they require dietary fat for absorption. Studies show that beta-carotene absorption from carrots can be increased 6-fold when a small amount of fat is consumed in the same meal.

This creates a natural synergy with nuts: when you consume carotenoid-rich dried apricots or mangoes alongside the healthy fats present in almonds or walnuts, you enhance carotenoid absorption significantly compared to eating the apricots alone. The fats stimulate bile acid secretion, which is necessary for forming the micelles that transport fat-soluble compounds across the intestinal wall.

Similarly, quercetin absorption appears to be enhanced when consumed with Vitamin C, and some polyphenols are better absorbed when consumed with fats. The whole-food matrix of nuts and dried fruits naturally provides these synergistic combinations. For strategic food pairings, explore our Dry Fruit Flavor Pairing Generator.

Gut Microbiota: Your gut bacteria are essential metabolic partners. Many polyphenols, such as lignans from flax seeds, are not active in their native form. They must first be metabolized by gut bacteria into their bioactive forms. Lignans are converted to enterolignans (enterodiol and enterolactone), and ellagitannins from walnuts are converted to urolithins.

This means a healthy, diverse gut microbiome is essential to unlock the full benefits of phytochemicals. Antibiotic use, poor diet, chronic stress, and other factors that disrupt the microbiome can impair your ability to metabolize and benefit from these compounds. Ironically, consuming phytochemical-rich foods also supports a healthy microbiome—creating a positive feedback loop.

Individual Variation: Genetic factors, age, gut health, and overall diet all influence how efficiently you absorb and metabolize phytochemicals. This is why population studies show average effects, but individual responses can vary significantly. Some people are efficient urolithin producers, others are not. Some people absorb carotenoids well, others poorly.

Strategies to Maximize Bioavailability

Soaking and Activation: Soaking nuts and seeds in water for several hours or overnight can reduce phytate content (a compound that binds minerals and reduces their absorption) and may improve the bioaccessibility of some phytochemicals. The term “activated” nuts refers to this soaking and sometimes sprouting process.

While soaking does leach some water-soluble nutrients into the soaking water (which is typically discarded), it can improve the digestibility of the nuts and may enhance mineral absorption. The effect on phytochemicals is mixed—some may be lost, others may become more bioavailable. For most people, the digestibility benefits outweigh minor nutrient losses. Our detailed guide on Soaking Nuts and Seeds covers the science and techniques.

Consume with Fats: For fat-soluble phytochemicals (carotenoids, Vitamin E), always consume with a source of dietary fat. The beauty of nuts is they provide their own fat, making them an ideal vehicle for dried fruits. A handful of almonds with dried apricots is nutritionally synergistic, not just a convenient snack combination.

Support Your Microbiome: Eat a diverse diet rich in fiber, minimize unnecessary antibiotic use, manage stress, and consider fermented foods. Your gut bacteria are the key to unlocking many phytochemical benefits. The fiber in dried fruits and nuts themselves acts as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial bacteria.

Don’t Rely on Supplements: Isolated, high-dose phytochemical supplements often have poor bioavailability and lack the synergistic matrix of whole foods. The entourage effect—all the compounds working together—appears crucial for optimal benefits. Plus, some isolated phytochemicals at high doses can have pro-oxidant effects rather than antioxidant effects, potentially causing harm.

Do Phytochemicals Work Better in Combination? The Synergy Hypothesis

A concept in functional food research suggests that health benefits of whole foods may come from synergistic interactions of multiple compounds rather than single isolated compounds. This is sometimes called the “entourage effect” or “food matrix effect.”

The hypothesis is plausible but remains incompletely understood. While some research supports additive or synergistic effects for certain antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of whole foods, mapping all interactions is not yet possible.

The Whole Food Hypothesis

A handful of mixed nuts and dried berries contains hundreds of different phytochemicals. Multiple types of flavonoids, phenolic acids, carotenoids, phytosterols, lignans, and terpenes may interact in various ways.

Some proposed interactions include enhanced absorption, protection from digestive degradation, and complementary mechanisms of action. However, these interactions are complex and not fully characterized. Research continues to examine these potential synergistic effects.

Evidence from Observational Studies and Clinical Trials

The PREDIMED (Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea) trial provides the strongest evidence for whole-food nut consumption. This Spanish study followed over 7,000 people at high cardiovascular risk for nearly 5 years.

One group consumed a Mediterranean diet supplemented with 30 grams of mixed nuts daily (walnuts, almonds, hazelnuts). This group showed approximately 30% reduced risk of major cardiovascular events compared to the control group.

This was whole food intervention, not isolated phytochemical supplementation. However, isolating which specific components or combinations of components provided the benefit remains challenging. The nuts provided a complex matrix of fats, proteins, fibers, vitamins, minerals, and hundreds of phytochemicals.

Attempts to recreate cardiovascular benefits with isolated components in supplement form have yielded mixed or negative results. High-dose alpha-tocopherol (Vitamin E) supplements in clinical trials showed no cardiovascular benefit and some studies suggested potential harm at very high doses.

The contrast between whole food and supplement outcomes may support the food matrix hypothesis, though alternative explanations exist including dose, form, and confounding lifestyle factors in observational data.

Practical Application: Diversity is Key

The synergy principle has a clear practical implication: eat a variety of nuts and dried fruits rather than focusing on a single “superfood.” A mix of walnuts (polyphenols), almonds (Vitamin E and flavonoids), pistachios (lutein), cashews (anacardic acids), dried apricots (carotenoids), prunes (phenolic acids), and berries (anthocyanins) provides a comprehensive phytochemical profile with overlapping and complementary benefits.

Our Interactive Trail Mix Builder helps you create nutritionally optimized combinations. For those following specific dietary patterns, our Homemade Granola and Muesli Guide shows how to incorporate diverse nuts and dried fruits into your daily routine.

The emerging science of nutritional metabolomics—studying how different food compounds interact in the body—continues to reveal the incredible complexity of whole food nutrition. The more we learn, the more we appreciate that reductionist approaches (isolating single compounds) miss the forest for the trees. The complexity is the point.

What Are the Safe Daily Limits for Nuts and Dried Fruits?

Concentrated nutrition comes with important considerations. Caloric density, potential sensitivities, and evidence-based portion sizes require understanding to prevent unintended consequences.

Myth 1: “More is Better” — The Caloric Density Reality

The same concentration effect that makes dried fruits phytochemical-rich also makes them calorie-dense. A cup of fresh grapes contains about 60 calories. That same amount of raisins? Approximately 450 calories. The volume is deceptively small for the caloric load.

This doesn’t make dried fruits “bad”—it makes them nutritionally powerful in small amounts. The problem arises when people consume them mindlessly in the same quantities they would fresh fruit. A small handful (30-50g) provides substantial nutrition. A large bowl consumed while watching TV can easily deliver 500+ calories.

Nuts face the same challenge. A handful of almonds (about 23 nuts or 30g) provides 170 calories—a perfect nutrient-dense snack. Three handfuls absent-mindedly consumed? Over 500 calories. For many people, this can undermine weight management efforts despite the nutritional quality.

Evidence-based recommendation: The PREDIMED study found cardiovascular benefits from approximately 30g of mixed nuts daily—about one small handful. This is a good baseline for most people. For dried fruits, 30-50g daily (about 3-5 dried apricots or 5-6 prunes) provides phytochemical benefits without excessive caloric intake. Our Portion Size Recommender provides personalized guidance based on your goals.

Risk 2: Sulfites in Dried Apricots and Other Fruits

Many commercially dried apricots, golden raisins, and other light-colored dried fruits are treated with sulfur dioxide or other sulfites to preserve color and prevent browning. For most people, this is harmless. For individuals with asthma or sulfite sensitivity, it can trigger respiratory symptoms, ranging from mild wheezing to severe bronchospasm.

Approximately 5-10% of people with asthma are sensitive to sulfites. If you have asthma and notice respiratory symptoms after consuming certain dried fruits, sulfites may be the culprit. The solution is simple: choose unsulfured varieties.

Unsulfured apricots are darker—brownish-orange rather than bright orange—but they retain their nutritional value including beta-carotene and polyphenols. They may have a slightly different flavor profile (sometimes described as more “caramelized”), but many people prefer them. Our guide on Sulphured vs Unsulphured Dry Fruits covers selection and storage.

Recommendation: If you have asthma, sulfite sensitivity, or simply prefer to avoid additives, look for packaging that states “no sulfites added” or “unsulfured.” Organic dried fruits are typically unsulfured by default.

Risk 3: Nut Allergies — A Serious Concern

Tree nut allergies affect approximately 1% of the population and can cause severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reactions (anaphylaxis). This is not a tolerance issue or a mild sensitivity—it’s a true immune-mediated allergy requiring strict avoidance.

Common allergens include almonds, walnuts, cashews, pistachios, pecans, and hazelnuts. Some people are allergic to only one or two types of nuts, while others react to all tree nuts. Peanuts (which are legumes, not tree nuts) cause a separate allergy, though people with peanut allergies may also have tree nut allergies.

If you have diagnosed nut allergies, there’s no safe amount to consume. Cross-contamination is also a concern—even products that don’t contain nuts may be processed in facilities that handle nuts. For risk assessment, our Allergy Risk Assessor provides guidance.

Recommendation: If you have nut allergies, focus on seeds (pumpkin, sunflower, chia, flax) which provide many similar nutrients and phytochemicals without the allergenic tree nut proteins. Always read labels carefully and carry an epinephrine auto-injector if prescribed.

Myth 4: “The Sugar in Dried Fruit Cancels Out the Benefits”

This oversimplification ignores the critical role of the food matrix. Yes, dried fruits contain concentrated natural sugars. But they also contain fiber, polyphenols, vitamins, and minerals that work together to modulate the glycemic response and provide protective effects.

Studies measuring the actual glycemic impact of dried fruits show that despite their sugar content, they often produce moderate glycemic responses. The fiber slows sugar absorption, and some polyphenols can inhibit carbohydrate-digesting enzymes, further moderating blood sugar spikes.

A systematic review published in Nutrition Journal found that dried fruit consumption was not associated with increased markers of diabetes risk and in some cases was associated with improved glycemic control. The key is portion control and consuming them as part of balanced meals rather than in isolation on an empty stomach.

Recommendation: For most people, 30-50g of dried fruit daily is reasonable. Those with diabetes should monitor their individual response, but blanket avoidance is not evidence-based. Pairing dried fruits with nuts (which provide fat, protein, and fiber) creates a more balanced snack that produces a lower glycemic response. Our Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Guide provides detailed data.

Risk 5: Brazil Nuts and Selenium Toxicity

This is a unique case worth mentioning. Brazil nuts are extraordinarily rich in selenium—a single nut can provide 70-90 μg, and the tolerable upper intake level for selenium is 400 μg daily for adults. Chronic excessive selenium intake can cause selenosis, characterized by hair loss, nail brittleness, garlic breath, fatigue, and neurological damage.

While selenium is an essential mineral and antioxidant, the dose makes the poison. Eating 2-3 Brazil nuts daily provides excellent selenium nutrition. Eating 10+ daily for extended periods risks toxicity.

Recommendation: Limit Brazil nuts to 2-3 per day (about 10g) to stay within safe selenium ranges while still benefiting from their unique nutritional profile. Our Micronutrient Calculator tracks selenium alongside other minerals.

Practical Daily Limits Summary

- Mixed nuts: 30g daily (about one small handful) based on PREDIMED trial

- Dried fruits: 30-50g daily (3-6 pieces depending on size)

- Brazil nuts specifically: 2-3 nuts daily maximum due to selenium content

- Flax seeds: 1-2 tablespoons ground daily provides lignans without excessive fiber

- Total combined: Most people do well with 50-80g total nuts and dried fruits daily

These are evidence-based guidelines for general health. Individual needs vary based on total caloric intake, activity level, health goals, and medical conditions. For personalized recommendations, consult our Nutrient Target Calculator or a registered dietitian.

What Are the Current Limitations in Phytochemical Research?

Understanding the limitations of current knowledge is essential for accurate interpretation of phytochemical science. Several significant knowledge gaps exist in this field.

Bioavailability and Human Translation Challenges

Most phytochemical research uses in vitro (cell culture) or animal models. These studies identify potential mechanisms and bioactive properties. However, translation to human health outcomes faces multiple challenges.

Bioavailability in humans is often low and highly variable. The amount consumed does not equal the amount absorbed or the amount reaching target tissues. Controlled feeding studies sometimes show limited postprandial effects despite high in vitro activity.

Individual differences in gut microbiota, genetic variants in metabolic enzymes, and overall dietary patterns create substantial variability in phytochemical metabolism and effects between people.

ORAC and In Vitro Antioxidant Measures

ORAC values and similar in vitro antioxidant capacity assays have major limitations. The USDA withdrew its ORAC database in 2012, specifically noting these values do not reliably predict in vivo antioxidant effects or health outcomes in humans.

In vitro antioxidant capacity does not account for absorption, metabolism, tissue distribution, or actual physiological effects. A compound with high ORAC value may have poor bioavailability or may be rapidly metabolized into inactive forms.

Limited Long-Term Human Clinical Trials

While epidemiological studies show associations between nut and fruit consumption and reduced disease risk, establishing causality requires controlled interventions. Long-term randomized controlled trials are expensive and logistically challenging.

Most intervention studies are short-term (weeks to months) and use surrogate markers rather than clinical endpoints. Long-term effects on outcomes like cancer incidence, neurodegenerative disease, or longevity remain largely observational.

Synergy and Food Matrix Effects

The synergy hypothesis is plausible and supported by some evidence. However, it remains incompletely characterized. Mapping hundreds of phytochemical interactions and their combined effects is extraordinarily complex.

Current analytical methods cannot fully capture all compounds in a food or predict their interactions. The specific combinations, ratios, and contexts that produce synergistic effects require further research.

Emerging Phytochemicals and Terpenoids

For compounds like ursolic acid, limonoids, and various terpenoids, human evidence is very limited. Most research is preclinical (cell culture or animal models). Health claims for these compounds are premature.

The amounts present in foods may be far below doses used in laboratory studies. Whether dietary levels provide meaningful biological effects in humans is largely unknown.

Variability in Phytochemical Content

Phytochemical content varies substantially based on multiple factors. Plant variety, growing conditions, ripeness at harvest, processing methods, and storage conditions all influence final phytochemical composition.

Published values represent averages or ranges from specific samples. Your actual dietary intake may differ significantly. Databases cannot capture this full variability.

Context Dependence and Confounding

In observational studies, people who eat more nuts and fruits often have other healthy behaviors. Disentangling the specific effects of phytochemicals from overall dietary patterns, physical activity, and other lifestyle factors remains challenging.

Phytochemical effects may be context-dependent, varying with dose, timing, food matrix, individual physiology, and interaction with medications or other dietary components.

Research Needs

The field requires more long-term human intervention trials with clinical endpoints. Better methods for assessing bioavailability and tissue-specific effects are needed. Understanding individual variability in phytochemical metabolism requires more research.

Despite these limitations, the overall evidence from epidemiological studies and some intervention trials supports beneficial effects of nut and dried fruit consumption as part of a balanced diet. The caution applies to overstating specific mechanisms or making precise claims about individual compounds.

Frequently Asked Questions on Phytochemicals in Dry Fruits

Q: What is the difference between a polyphenol and a flavonoid?

A polyphenol is a broad chemical class of plant compounds characterized by multiple phenol units. A flavonoid is the largest and most famous sub-group within the polyphenol family. Therefore, all flavonoids are polyphenols, but not all polyphenols are flavonoids. Other polyphenol subclasses include phenolic acids, lignans, and stilbenes.

Q: Are phytochemicals considered antioxidants?

Many, but not all, phytochemicals have antioxidant properties. Polyphenols, carotenoids, and some terpenoids can neutralize harmful free radicals through direct antioxidant activity. However, phytochemicals also work through other mechanisms including modulating gene expression (Nrf2 pathway), reducing inflammation (inhibiting NF-κB), and influencing hormone signaling. Antioxidant activity is one important function, but it’s not the complete picture.

Q: Which dry fruit has the highest antioxidant score?

Based on ORAC (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity) scores, prunes rank exceptionally high—often exceeding 8,000 μmol TE per 100g. Dried berries (blueberries, cranberries) also rank very highly, typically in the 5,000-9,000 range depending on variety. Raisins score around 3,000-4,000. These values reflect dense concentrations of polyphenols like anthocyanins and phenolic acids.

Q: Can I get enough phytochemicals from supplements instead of food?

Research strongly suggests that benefits come from consuming phytochemicals in their natural whole-food matrix, due to synergistic effects. Isolated, high-dose phytochemical supplements have not been shown to provide the same benefits as whole foods and can sometimes be harmful. The PREDIMED trial showed 30% cardiovascular risk reduction from whole nuts—a benefit not replicated by isolated supplements. The food matrix appears crucial.

Q: How do phytosterols in nuts help lower cholesterol?

Phytosterols are structurally similar to cholesterol. In the small intestine, they compete with dietary cholesterol for absorption into micelles—the transport structures that carry cholesterol into the bloodstream. This competition effectively blocks some cholesterol from being absorbed, leading to its excretion. Clinical trials show that 2-3g of phytosterols daily can reduce LDL cholesterol by 8-10%.

Q: Are roasted nuts still high in phytochemicals?

Yes, roasting at moderate temperatures preserves most phytochemicals in nuts. While some heat-sensitive vitamins (like thiamin) may decrease, polyphenols and phytosterols remain largely intact with light to moderate roasting (140-160°C). Very high heat or prolonged roasting can cause some degradation, but dry-roasted or lightly roasted nuts retain significant phytochemical content. The improved palatability often leads to better adherence to nut consumption.

Q: Is the skin of the almond important?

Yes, the brown skin contains a substantial proportion of almond flavonoids. Research indicates the skin is the primary reservoir of proanthocyanidins, flavonols, and phenolic acids that provide antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits. The exact percentage varies by cultivar and analytical method, but blanched almonds (skin removed) lose most of this phytochemical-rich component. For maximum benefit, consume almonds with skins intact.

Q: Do cashews have polyphenols?

Yes, cashews contain polyphenols including proanthocyanidins and catechins, though at lower concentrations than almonds or walnuts. Their unique contribution is anacardic acids—phenolic lipids with demonstrated antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties in laboratory studies. Cashews provide a different phytochemical profile that complements other nuts in a mixed nut diet.

Q: What is ellagic acid good for?

Ellagic acid is a polyphenol found in walnuts, berries, and pomegranates with strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. It’s converted by gut bacteria into urolithins, which have been shown in research to promote mitophagy (clearance of damaged mitochondria) and may support cellular energy production and healthy aging. Research also explores its potential role in cardiovascular protection and cellular health.

Q: How many walnuts should I eat a day?

The PREDIMED study used approximately 30g of mixed nuts daily (about 7 walnut halves), which showed significant cardiovascular benefits. For specific walnut consumption, 7-14 walnut halves (roughly 30-60g) daily provides substantial omega-3 fatty acids and polyphenols without excessive calories. Start with a smaller amount and adjust based on your total caloric needs and response.

Q: Does drying fruit destroy Vitamin C?

Yes, Vitamin C is highly sensitive to heat and oxidation, so conventional drying methods significantly reduce it. Fresh apricots contain about 10mg of Vitamin C per 100g, while dried apricots contain less than 1mg. However, other nutrients and phytochemicals (carotenoids, polyphenols, minerals) are concentrated and well-preserved during drying. Dried fruits aren’t a good Vitamin C source, but they excel at providing other protective compounds.

Q: Are sulfur-free dried fruits better?

For most people, sulfur dioxide in dried fruits is safe. However, individuals with asthma or sulfite sensitivity should choose unsulfured varieties to avoid potential respiratory symptoms. Unsulfured fruits are darker in color but retain their nutritional value including phytochemicals. The choice often comes down to personal preference and any sensitivities rather than inherent nutritional superiority.

Q: What is the best time to eat dry fruits?

There’s no single “best” time—it depends on your goals. For sustained energy, consume them mid-morning or afternoon with nuts to provide steady fuel. For workout recovery, within 30-60 minutes post-exercise pairs their quick-digesting carbs with protein from nuts. For weight management, portion them out rather than eating directly from the bag. Timing matters less than portion control and pairing with complementary foods.

Q: Do almonds lose nutrients when soaked?

Soaking causes minor losses of some water-soluble nutrients into the soaking water, but it improves digestibility and may enhance mineral absorption by reducing phytate content. The phytochemicals in the skin remain largely intact. For most people, the digestibility benefits outweigh the small nutrient losses. If you soak almonds, keep the skins on to preserve flavonoids.

How we reviewed this article:

▼This article was reviewed for accuracy and updated to reflect the latest scientific findings. Our content is periodically revised to ensure it remains a reliable, evidence-based resource.

- Current Version 27/11/2025Written By Team DFDEdited By Deepak YadavFact Checked By Himani (Institute for Integrative Nutrition(IIN), NY)Copy Edited By Copy Editors

Our mission is to demystify the complex world of nutritional science. We are dedicated to providing clear, objective, and evidence-based information on dry fruits and healthy living, grounded in rigorous research. We believe that by empowering our readers with trustworthy knowledge, we can help them build healthier, more informed lifestyles.