In the quest for healthier eating, sugar has become a primary focus of concern. This often leads to confusion when it comes to dry fruits: they are fruits, which are healthy, but they are also sweet. Are they a wholesome food or simply a “natural” candy? This guide provides a comprehensive explanation of the crucial difference between the naturally occurring sugars inherent in whole dry fruits and the added sugars found in many commercially processed fruit products, detailing the health implications of each.

Defining Our Scientific and Health Focus

This article focuses on differentiating natural and added sugars in the context of dry fruit products and explaining their respective health impacts. CRITICAL DISCLAIMER: The information provided is for educational purposes and is not a substitute for personalized medical or dietary advice. Individuals with health conditions like diabetes, pre-diabetes, or insulin resistance must consult with a qualified healthcare professional or Registered Dietitian for personalized dietary management. This guide aims to foster consumer literacy, not to prescribe diets.

Key Takeaways

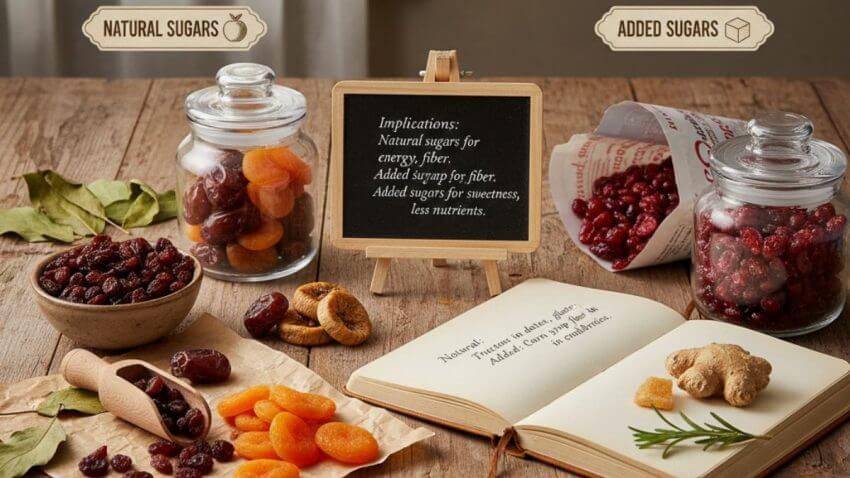

- Natural vs. Added Sugar is the Key Distinction: Natural (intrinsic) sugars are part of the fruit’s original structure. Added (extrinsic) sugars are put in during processing for flavor or texture.

- The “Whole Food Matrix” Matters: The natural sugars in unsweetened dry fruits come packaged with dietary fiber, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. This fiber significantly slows down sugar absorption and modulates the body’s metabolic response.

- Added Sugars are “Empty Calories”: Added sugars, like high-fructose corn syrup or sucrose, provide calories with little to no other nutritional value and are linked to negative health outcomes when consumed in excess.

- Read the Ingredient List First: This is the most reliable way to identify added sugars. Sugar has many names (e.g., dextrose, cane syrup, fruit juice concentrate). If it’s on the list, it has been added.

- Use the “Added Sugars” Line: The Nutrition Facts panel now separates “Total Sugars” from “Added Sugars,” making it easier than ever for consumers to see how much sugar is not naturally occurring.

What Exactly Are the Natural Sugars in Fruit?

The sweetness in whole, unsweetened fruit comes from naturally occurring, or intrinsic, sugars that the plant produces during photosynthesis. These are not chemically different from processed sugars, but their source and context are everything. A food scientist would identify the main types as:

- Fructose: Often called “fruit sugar,” it is the primary source of sweetness in most fruits.

- Glucose: The body’s primary source of energy for cells.

- Sucrose: This is the chemical name for table sugar, but it is also found naturally in many fruits as a combination of one glucose and one fructose molecule.

Crucially, in a whole fruit, these sugar molecules are contained within the plant’s fibrous cellular structure. This structure is what makes them part of a healthy, whole-food package. Understanding the natural sugar profile in different dry fruits can help you make informed dietary choices.

How Does Dehydration Affect a Fruit’s Sugar Content?

The process of dehydration does not add sugar to fruit; it simply removes water, which dramatically concentrates the fruit’s natural sugars and all other solid components.

Imagine a cup of fresh grapes and a quarter-cup of raisins. They may contain a similar number of grapes, but the raisins have had nearly all their water removed. This means the sugars, fiber, and minerals are concentrated into a much smaller, denser, and more calorie-rich package. This is why dry fruits are so sweet and why portion control is essential, even though the sugar is natural.

The concentration process fundamentally changes the caloric density of dried fruits, making them more energy-dense than their fresh counterparts. To better understand how water removal affects nutritional properties, explore our detailed guide on fruit dehydration principles and property changes.

Why Do Manufacturers Add Sugar to Some Dry Fruit Products?

Manufacturers add sugar to certain dried fruit products for several reasons that go beyond simple sweetness, often related to improving flavor, texture, and preservation.

A food scientist would explain these key motivations:

- Palatability: Some fruits, most notably cranberries, are naturally very tart and require some added sugar to be palatable for the majority of consumers.

- Texture and Mouthfeel: The process of infusing fruit with sugar syrup before drying (osmotic dehydration) can result in a softer, moister, and chewier final product that some consumers prefer.

- Preservation: Sugar is a preservative. At high concentrations, it binds to water molecules, making them unavailable for microbial growth and thus extending shelf life. This is the principle behind candied fruits, an extreme example of this practice.

For those interested in making dried fruits at home without added sugars, consider learning how to use a food dehydrator or explore oven dehydration methods for complete control over ingredients.

How Can You Identify Added Sugars on a Food Label?

To be an informed consumer, you must become a detective. The clues to identifying added sugars are found in two places: the ingredient list and the nutrition facts panel.

Step 1: Decode the Ingredient List

This is your most reliable tool. Ingredients are listed in descending order by weight. A consumer advocate would advise you to look for sugar’s many aliases:

- Common Sugar Synonyms:

- Sucrose, Dextrose, Fructose, Maltose, Glucose

- Corn-Based Sweeteners:

- High-fructose corn syrup, Corn syrup solids, Glucose-fructose syrup

- Cane-Based Sweeteners:

- Cane sugar, Cane juice, Evaporated cane juice, Invert sugar

- Natural Sweeteners:

- Brown rice syrup, Maple syrup, Honey, Agave nectar, Treacle

- Fruit-Based Sweeteners:

- Fruit juice concentrate, Apple juice concentrate (when used as a sweetener, this is considered an added sugar)

Understanding how to read dry fruit labels is a fundamental skill for making healthier purchasing decisions.

Step 2: Interpret the Nutrition Facts Panel

Thanks to updated FDA labeling rules, this is now easier than ever. Look for these two lines:

- Total Sugars: This includes both the natural sugars from the fruit and any sugars that have been added.

- Includes Xg Added Sugars: This line is indented below “Total Sugars” and tells you exactly how many grams of the total sugar content come from added sources. This is your key indicator. Your goal is to choose products where this number is zero or as low as possible.

Understanding Claims on Packaged Dried Fruit

Marketing language on packaging can be misleading. Here’s what common claims actually mean:

- No Sugar Added / Unsweetened

- No sugars or sugar-containing ingredients (including juice concentrates) added during processing. Natural fruit sugars only.

- Reduced Sugar

- At least 25% less sugar than a reference product. Still can be high in total sugars.

- Lightly Sweetened / Sweetened with Fruit Juice

- Marketing language—still added sugars if a syrup or juice concentrate is used. Always confirm on the “Includes Added Sugars” line.

- Juice-Infused

- If fruit juice concentrate is used to sweeten, it counts as added sugar. Check both the ingredient list and the “Includes Added Sugars” declaration.

Regulatory Definitions: FDA, WHO, and EU Standards

Different health authorities define and regulate sugar labeling in distinct ways. Understanding these differences helps you interpret labels from various regions:

FDA “Added Sugars” (United States)

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires manufacturers to list “Added Sugars” separately on the Nutrition Facts panel. This includes all sugars added during processing, including syrups, honey, and fruit juice concentrates used as sweeteners.

WHO “Free Sugars” (International)

The World Health Organization uses the term “free sugars” to encompass all sugars added to foods, plus sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, and fruit juices/concentrates. Crucially, the WHO definition does not include the intrinsic sugars within whole fruits (fresh or dried). The WHO recommends limiting free sugar intake to less than 10% of total daily energy intake.

EU “Sugars” Labeling

European Union nutrition labels list “Sugars” (which includes both natural and added sugars combined) but do not yet mandate a separate “added sugars” declaration. Consumers must rely primarily on the ingredient list to identify added sweeteners.

Edge Cases and Clarifications

- Fruit juice concentrate as sweetener vs. standardization: When concentrate is added primarily to sweeten, it’s an added sugar. When used to standardize acidity or restore flavor lost during processing of the same fruit, classification can be nuanced.

- Purees vs. concentrates: If a dried fruit product contains only the purée of that fruit (no additional sweeteners), the sugars remain intrinsic. Any additional sweeteners make those added sugars.

Quantitative Sugar Comparison in Common Dried Fruits

Understanding the actual sugar content in various dried fruit products helps put nutrition labels in context. The following table compares typical sugar values per 40-gram serving (approximately one small handful):

| Product (40 g serving) | Total Sugars | Includes Added Sugars |

|---|---|---|

| Raisins (unsweetened) | 28–30 g | 0 g |

| Dates (unsweetened) | 27–29 g | 0 g |

| Dried figs (unsweetened) | 24–26 g | 0 g |

| Dried apricots (unsweetened) | 16–18 g | 0 g |

| Dried cranberries (sweetened) | 26–28 g | 22–24 g |

| Dried mango (sweetened) | 28–32 g | 10–16 g |

| Banana chips (fried, sugared) | 18–22 g | 8–12 g |

Notice that naturally sweet fruits like dates and raisins contain high total sugars but zero added sugars, while cranberries—naturally tart—contain mostly added sugars. For a deeper analysis of sugar content, use our natural sugar profile calculator.

What Are the Health Implications of Natural vs. Added Sugars?

The metabolic and health impacts of sugar are profoundly influenced by its context. The body’s response to the intrinsic sugars in a whole dry fruit is very different from its response to the extrinsic, or added, sugars in a processed snack.

The “Whole Food Matrix”: Why Fiber Matters

A Registered Dietitian specializing in sugar metabolism would emphasize the importance of the food matrix. In an unsweetened dried apricot, the natural sugars are bound within a matrix of dietary fiber. This fiber slows down digestion and the release of sugar into the bloodstream, leading to a more moderate glycemic response.

The presence of dietary fiber in dry fruits not only moderates blood sugar but also supports digestive health and satiety. Understanding the nutrient density of dry fruits reveals how fiber, vitamins, and minerals work synergistically with natural sugars.

Health Risks of Excessive Added Sugar

Diets high in added sugars are linked by major health bodies like the American Heart Association (AHA) to a host of health problems, including weight gain, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. These empty calories contribute to energy imbalance without providing beneficial fiber and micronutrients.

Research shows that excessive fructose from added sugars (particularly high-fructose corn syrup) can stress the liver and contribute to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. However, the fructose consumed from whole fruit is not associated with these risks due to the co-presence of fiber and lower concentration per serving.

Glycemic Response: How Fiber Affects Blood Sugar

The glycemic index (GI) measures how quickly a food raises blood sugar, while glycemic load (GL) accounts for both the quality and quantity of carbohydrates in a serving. Dried fruits generally have a low to medium GI due to their fiber content, even though they’re high in natural sugars.

Approximate Glycemic Values for Common Dried Fruits

| Dried Fruit (30-40 g portion) | Glycemic Index (GI) | Glycemic Load (GL) |

|---|---|---|

| Dates | 42–55 (Medium) | 18–25 (Medium-High) |

| Raisins | 54–64 (Medium) | 15–20 (Medium) |

| Dried apricots | 30–32 (Low) | 9–12 (Low) |

| Prunes | 29–38 (Low) | 10–13 (Low-Medium) |

For personalized glycemic impact calculations, explore our glycemic load calculator.

Special Note on Sorbitol in Prunes and Apricots

Prunes and dried apricots naturally contain sorbitol, a sugar alcohol that contributes to their lower glycemic response. Sorbitol is absorbed more slowly than regular sugars, which helps moderate blood sugar spikes. However, in larger amounts (typically more than 50-60 grams of dried fruit), sorbitol can cause gastrointestinal discomfort, including bloating and a laxative effect.

How Fiber Modulates Sugar Absorption

The soluble fiber in dried fruits forms a viscous gel in the stomach and small intestine. This gel physically slows the movement of food through the digestive tract and creates a barrier that delays sugar absorption. The result is a more gradual rise in blood glucose and a reduced insulin response compared to consuming an equivalent amount of added sugar.

Processing Methods and Sugar Pathways

Understanding how dried fruits are processed helps explain why some products contain added sugars while others don’t.

Osmotic Dehydration (Syrup Infusion)

In osmotic dehydration, fresh fruit is immersed in a concentrated sugar syrup before the drying process. The high sugar concentration outside the fruit draws water out through osmosis, while simultaneously infusing the fruit with sugar. This process creates a softer, moister, and sweeter final product. This is the primary method used for sweetened cranberries, some mango products, and candied fruits.

Candied Fruits vs. Simply Dried

There’s a spectrum of processing intensity:

- Simply dried: Water removed through heat and airflow, no added ingredients. Examples: most raisins, prunes, unsweetened apricots.

- Juice-infused: Fruit soaked in fruit juice concentrate before drying. Still contains added sugars, despite the “natural” source.

- Sugar-infused: Fruit soaked in sugar syrup before drying. Examples: sweetened cranberries, some papaya.

- Candied/glacéd: Fruit repeatedly soaked in increasingly concentrated sugar syrups over several days, resulting in a translucent, very sweet product. Examples: candied cherries, citrus peels.

Quick Decision Guide for Ingredient Lists

Use this mental flowchart when reading labels:

- If ingredient list shows only the fruit name → No added sugars

- If you see “juice-infused” or “sweetened with fruit juice” + “concentrate” in ingredients → Added sugar (despite natural source)

- If any form of syrup, sugar, or honey appears → Obviously added sugar

- If label says “no sugar added” but ingredients include “juice concentrate” → Check if it’s the same fruit (might be for acidity) or a different fruit (likely added sugar)

Which Dry Fruit Products Often Contain Added Sugars?

Knowing which products are common culprits for added sugars can help you shop more efficiently.

Almost Always Sweetened

Dried cranberries are the most common example. Due to their natural tartness and low sugar content (only about 4 grams per 100 grams when fresh), they are almost always processed with added sugar or fruit juice concentrate to make them palatable. A typical serving may contain 22-24 grams of added sugar out of 26-28 grams total sugar.

Frequently Sweetened

- Dried mango and pineapple: Some varieties of these tropical fruits are sweetened to enhance flavor and create a chewier texture. Always check labels, as unsweetened versions are also available.

- Banana chips: Frequently fried in oil and coated with sugar or honey. The combination of added fat and sugar significantly increases calorie density.

- Papaya and kiwi: Often candied or sweetened, especially when sold in decorative packaging or as confections.

Typically Unsweetened

These fruits are naturally sweet enough that they are very rarely sold with added sugars:

- Raisins: Standard raisins (Thompson seedless, golden, or black) typically contain only grapes and possibly sulfur dioxide as a preservative.

- Prunes (dried plums): Naturally sweet and rarely sweetened. Ingredient list should just say “pitted plums” or “dried plums.”

- Dates: Among the sweetest dried fruits, dates never need additional sugar. Any processing is typically limited to pitting and pasteurization.

- Figs: Naturally high in sugar and typically sold without additives beyond possible sulfites.

- Unsulphured dried apricots: Most apricots are sold without added sugar, though they may contain sulfur dioxide to preserve color.

Always verify with the ingredient list, but this general guide can help you know when to be extra vigilant. Compare different dry fruits side-by-side to understand their nutritional profiles.

Portion Context and Practical Serving Guidance

Even unsweetened dried fruits require portion awareness due to their concentrated sugar and calorie content.

Evidence-Based Serving Guidance

Nutrition experts generally recommend:

- Standard serving: 30–40 grams of dried fruit (about 1/4 cup or a small cupped handful) is roughly equivalent to one small fresh fruit in terms of nutrient content.

- Visual guide: A small cupped handful (what fits in your palm when fingers are slightly curved) is approximately 30 grams for most dried fruits.

- Daily limit: 1–2 servings per day is appropriate for most adults as part of a balanced diet.

Use our portion size recommender for personalized serving suggestions based on your needs.

Smart Pairing to Moderate Glycemic Impact

Combining dried fruits with protein, fat, or both significantly moderates the blood sugar response:

- Good pairing: 30 g raisins + 28 g almonds → The healthy fats, protein, and additional fiber from almonds slow sugar absorption and increase satiety. Explore healthy fats in nuts for optimal combinations.

- Better pairing: 30 g unsweetened apricots + plain Greek yogurt → Protein and acidity from yogurt, plus additional viscosity, create an even flatter glycemic curve and support gut health.

- Excellent pairing: A small handful of dates + almond butter → Healthy fats and protein from nut butter provide sustained energy and prevent blood sugar spikes.

For balanced snack ideas, check our guide to creating homemade trail mixes or use the interactive trail mix builder to create custom combinations.

Fresh vs. Dried: Satiety and Energy Density

Understanding the difference between fresh and dried fruit helps explain why portion control is crucial for dried varieties:

| Factor | Fresh Fruit | Dried Fruit |

|---|---|---|

| Water content | 80–95% | 15–25% |

| Volume per 100 calories | Large (high volume) | Small (low volume) |

| Chewing time | Longer | Shorter |

| Stomach stretch signals | Strong (triggers fullness) | Weak (easy to overeat) |

| Satiety per calorie | Higher | Lower |

Compare the nutritional differences using our fresh vs. dried fruit comparison tool.

When to Prefer Fresh Fruit

Fresh fruit is generally preferable when:

- You’re trying to manage overall calorie intake or lose weight

- You want to feel fuller on fewer calories

- You’re very sensitive to blood sugar fluctuations

- Hydration is a priority (such as during hot weather or after exercise)

- You have unlimited access to fresh, ripe fruit in season

Dental Health Considerations

The concentrated sugars and sticky texture of dried fruits create unique dental health concerns that deserve attention.

Why Dried Fruits Pose Dental Risks

Dried fruits have several properties that increase cariogenic (cavity-causing) potential:

- Sticky texture: Dried fruits adhere to teeth and get lodged between them, providing a prolonged sugar source for bacteria.

- Concentrated sugars: High sugar density means more fuel for cavity-causing bacteria in the mouth.

- Low water content: Fresh fruits stimulate saliva production (which helps neutralize acids and wash away sugars); dried fruits do not.

- Extended contact time: The sticky residue can remain on teeth for hours if not removed.

Prevention Strategies

Protect your dental health while enjoying dried fruits:

- Rinse immediately: Swish water vigorously after eating dried fruits to dislodge stuck particles.

- Pair strategically: Eat dried fruits with cheese or nuts. Cheese neutralizes acids and provides calcium; nuts require more chewing, which stimulates protective saliva.

- Avoid grazing: Eat dried fruits as part of a meal or defined snack, not throughout the day. Continuous snacking means constant acid exposure to tooth enamel.

- Brush properly: Wait 30 minutes after eating (to avoid brushing acid into enamel), then brush and floss thoroughly.

- Chew sugar-free gum: If brushing isn’t immediately possible, sugar-free gum stimulates saliva production and helps clean teeth.

Children and Special Populations

Different groups have unique considerations when it comes to dried fruit consumption.

Guidance for Children

Portion sizes for kids: Children require smaller servings—typically 15–20 grams (about 1–2 tablespoons) for young children and 20–30 grams for older children and teens.

Choking hazards: Dried fruits pose a choking risk for children under 4 years. Whole grapes, large raisins, and chewy dried fruits should be avoided or cut into very small pieces. Never leave young children unattended while eating dried fruits.

Lunchbox tips: Choose unsweetened varieties and pair with protein-rich foods like cheese cubes or nut butter (if no allergies). Pack wet wipes or include a small water bottle to encourage rinsing after eating. For creative, healthy snack ideas, explore our kids’ healthy snack box builder.

Hyperpalatable sweetened products: Sweetened dried cranberries, yogurt-covered raisins, and candy-like dried fruit snacks can train young palates to expect extreme sweetness. Prioritize unsweetened options to develop healthier taste preferences.

Diabetes and Insulin Resistance

Individuals with diabetes or pre-diabetes should approach dried fruits with particular care:

- Strict portion control: Limit to 15–20 grams per serving and always pair with protein or healthy fat.

- Monitor blood glucose: Test blood sugar 1–2 hours after eating dried fruits to understand your personal response.

- Prioritize low-GI options: Choose dried apricots or prunes over dates or raisins when possible.

- Never eat alone: Always combine with nuts, seeds, or other foods that slow glucose absorption.

- Consult your healthcare team: Work with a Registered Dietitian or Certified Diabetes Educator to determine if and how dried fruits fit into your meal plan.

Calculate the glycemic impact of your snack choices with our net carb and glycemic load calculator.

Pregnancy and Nursing

Dried fruits can be beneficial during pregnancy and lactation due to their concentrated iron, folate, and fiber content. However, practice portion control to avoid excessive weight gain. Prunes are particularly helpful for preventing pregnancy-related constipation. Explore pregnancy nutrition support for tailored guidance.

How Can You Choose Healthier, Low-Sugar Dry Fruit Options?

A consumer advocate would offer these practical tips for making the healthiest choices at the store:

- Prioritize the Ingredient List: Make it a habit to read this first. Look for a single ingredient: the fruit itself. If you see multiple ingredients, scrutinize each one.

- Focus on “Added Sugars” on the Nutrition Panel: Aim for products with “0g” on the “Includes Added Sugars” line. This is your most reliable indicator.

- Choose Whole Over Processed: Select whole dried fruits (like apricots or dates) over pureed and reformed products (like fruit leathers or roll-ups), which are more likely to contain added sugars and have lost some fiber structure.

- Be Skeptical of Front-of-Package Claims: Words like “natural,” “fruit snack,” or “made with real fruit” are marketing terms. Let the Nutrition Facts and ingredient list be your guide.

- When in Doubt, Choose Organic: While not a guarantee against added sugar, certified organic products are less likely to contain a long list of additives and must meet stricter processing standards.

- Buy from bulk bins with caution: While often more affordable, bulk dried fruits may not have complete labeling. Ask store staff for ingredient information or nutrition data.

- Consider freeze-dried alternatives: Freeze-dried fruits retain more of their original volume and water content, making portion control easier and reducing the concentration effect on sugars.

- Check for sulfites: While not related to sugar, sulfur dioxide preservatives (found in many apricots and golden raisins) can trigger reactions in sensitive individuals. Look for “unsulphured” options if this is a concern. Learn more about sulphured vs. unsulphured dry fruits.

Non-Sugar Sweeteners and Sugar Alcohols in Dried Fruit Products

Some “low-sugar” or “no-sugar-added” dried fruit products use alternative sweeteners.

Where Non-Sugar Sweeteners Appear

You might find these in:

- Diet or reduced-sugar dried fruit snacks

- Fruit leather products marketed to diabetics

- Some premium or specialty dried fruit blends

Common sweeteners include: stevia, monk fruit extract, erythritol, xylitol, and sorbitol (though sorbitol also occurs naturally in some fruits).

Labeling Note

Non-nutritive sweeteners (stevia, monk fruit) and sugar alcohols are not counted in the “Added Sugars” line on the Nutrition Facts panel. They appear separately or are listed only in the ingredient list.

Tolerance Considerations

Sugar alcohols can cause gastrointestinal effects in some people:

- Bloating, gas, and diarrhea are possible with intake above 10–20 grams per day

- Tolerance varies widely between individuals

- Erythritol is generally better tolerated than sorbitol or xylitol

- Start with small amounts to assess your personal tolerance

Smart Culinary Swaps and Recipe Ideas

You can enjoy the natural sweetness of dried fruits while avoiding added sugars with these practical swaps and recipes.

Smart Ingredient Swaps

- In baking: Replace up to 50% of granulated sugar with finely chopped dates or date paste. This adds fiber, minerals, and a rich caramel flavor while reducing refined sugar.

- For breakfast: Skip sweetened dried cranberries in your oatmeal; use unsweetened dried cherries or chopped apricots instead, paired with a sprinkle of cinnamon.

- In trail mix: Choose raw or dry-roasted unsalted nuts, unsweetened coconut flakes, and unsweetened dried fruit. Skip chocolate chips or yogurt-covered items. Create your own with our interactive trail mix builder.

- For desserts: Combine unsweetened dried fruit with 85% or higher dark chocolate. The bitterness of the chocolate balances the fruit’s natural sweetness without added sugar.

No-Added-Sugar Recipe Ideas

Energy Bites (Makes 12–15 balls):

- 1 cup pitted dates

- 1 cup unsweetened raisins or dried figs

- ½ cup natural peanut or almond butter

- 1 cup rolled oats

- ¼ cup ground flaxseed

- Optional: 2 tablespoons cacao nibs or unsweetened cocoa powder

Process dates in a food processor until sticky. Add remaining ingredients and pulse until combined. Roll into balls and refrigerate. Each bite provides sustained energy from natural sugars, fiber, and healthy fats. Get more ideas from our energy ball creator tool.

Homemade Fruit and Nut Bars:

Combine equal parts chopped unsweetened dried apricots, dried figs, almonds, and walnuts. Press firmly into a parchment-lined pan and refrigerate until firm. Cut into bars for portable snacks with zero added sugars. Design custom bars with our energy bar recipe creator.

Breakfast Parfait:

Layer plain Greek yogurt with chopped unsweetened dried apricots, a handful of granola (check for added sugars), and a sprinkle of chopped walnuts. The protein from yogurt and nuts balances the fruit’s natural sugars perfectly.

Flavor Pairing Guide

Enhance dried fruits naturally without adding sugar by pairing with complementary flavors:

- Dates: Pair with tahini, almond butter, sea salt, or wrap with prosciutto for a savory-sweet contrast

- Dried apricots: Excellent with goat cheese, pistachios, or in savory Moroccan-style tagines

- Raisins: Combine with curry spices, use in pilaf, or add to chicken salad with celery and walnuts

- Prunes: Wrap with bacon, pair with pork dishes, or cook with red wine for a sophisticated sauce

- Figs: Match with blue cheese, balsamic vinegar, or fresh rosemary

Discover more combinations with our flavor pairing generator.

Storage and Handling Tips

Proper storage extends shelf life and maintains quality, particularly for sweetened dried fruits which can be stickier and more prone to issues.

Optimal Storage Conditions

- Airtight containers: Sweetened dried fruits are stickier and attract more moisture, increasing mold risk. Store in truly airtight containers.

- Cool, dark location: A pantry away from heat sources is ideal. Heat accelerates quality degradation.

- Refrigeration: Extends shelf life significantly, especially for opened packages. Most dried fruits keep 6–12 months refrigerated.

- Freezing: For long-term storage (up to 18 months), freeze dried fruits in portions. They remain pliable even when frozen and can be used directly from the freezer.

- Pre-portioning: Divide bulk purchases into single-serving containers to prevent repeated exposure to air and moisture, and to help with portion control.

Learn more with our comprehensive shelf life guide and shelf life estimator tool.

Frequently Asked Questions on Sugar in Dry Fruits

Are “no sugar added” and “unsweetened” the same thing?

Yes, these terms generally mean the same thing: no external sugars or sugar-containing ingredients were added during processing. However, the product will still contain its own natural sugars from the fruit itself. Always verify by checking that the “Includes Added Sugars” line shows “0 g” and that the ingredient list contains only the fruit.

Is coconut sugar better than regular sugar?

No, coconut sugar is metabolically similar to regular table sugar. While it is less refined and may contain trace minerals, your body processes the sugars in coconut sugar in much the same way as regular sucrose. It is considered an “added sugar” when used in products and offers no significant health advantage over other sweeteners.

Are sugar alcohols like sorbitol considered added sugar?

No, sugar alcohols are not classified as added sugars on nutrition labels. Sugar alcohols (like sorbitol, xylitol, and erythritol) are a type of sweetener with fewer calories that are metabolized differently from regular sugars. They are listed separately on labels and are not included in the “Added Sugars” value. Interestingly, prunes and dried apricots naturally contain sorbitol as part of their intrinsic composition.

Why are dried cranberries almost always sweetened?

Fresh cranberries have a very low natural sugar content (only about 4 grams per 100 grams) and are intensely tart and acidic. They require added sugar to balance this tartness and make them palatable for most consumers. It is nearly impossible to find truly unsweetened dried cranberries in mainstream markets.

What is fruit juice concentrate?

Fruit juice concentrate is fruit juice that has had most of its water removed through evaporation. When it is used to sweeten another food product (even another fruit product), it is classified as an “added sugar” by health and regulatory bodies including the FDA and WHO. Don’t be misled by “sweetened with fruit juice”—it’s still added sugar.

Are “juice-infused” dried fruits free of added sugar?

Usually no. If fruit juice concentrate is used to sweeten, it counts as added sugar. Check the “Includes Added Sugars” line on the Nutrition Facts panel. Even though juice concentrate comes from fruit, when used as a sweetening agent for a different product, it functions as an added sugar and should be limited.

Do fruit purées used in leathers count as added sugar?

If it’s just the fruit purée alone, it’s intrinsic sugar. If additional sweeteners are added, those are added sugars. Check the ingredient list carefully. A fruit leather made from 100% pureed strawberries contains only natural sugars. But if the ingredients include “strawberry puree, apple juice concentrate, sugar,” then it contains added sugars from both the concentrate and the sugar.

Is coconut sugar or honey “better” in dried fruit products?

No, they are still added sugars and are metabolically similar to regular sucrose. Any perceived benefit is mostly about taste preference or minor trace nutrients—not a health advantage. When honey or coconut sugar appears in dried fruit ingredient lists, count them as added sugars and consider products without them.

Why do some labels show 0 g added sugar but taste very sweet?

That’s the fruit’s own intrinsic sugar, which becomes highly concentrated when water is removed during drying. Verify the ingredients list; if there’s only the fruit listed (e.g., “dried dates” or “raisins”), the 0 g added sugars claim is legitimate. Dates, for example, can be 60–70% sugar by weight naturally, making them intensely sweet without any additives.

Do all dried mangoes have added sugar?

Not all, but many do. It is important to check the label carefully, as some brands add sugar for extra sweetness and a chewier texture, while others sell unsweetened versions that rely solely on the mango’s natural sugars. The “Includes Added Sugars” line and ingredient list will tell you definitively.

Are prunes usually sweetened?

No, prunes (dried plums) are naturally very sweet and are almost never sold with added sugars. Their ingredient list should simply say “pitted plums” or “dried plums,” possibly with the addition of potassium sorbate as a preservative. Prunes are one of the safest dried fruits to buy without worrying about added sweeteners.

Is the sugar in fruit bad for your liver?

The high levels of fructose in added sugars like high-fructose corn syrup can stress the liver when consumed in excess. However, the fructose consumed from whole fruit—fresh or dried—is not associated with these risks. The fiber, antioxidants, and overall lower fructose concentration in whole fruit protect against the negative hepatic effects seen with refined added sugars.

How does fiber help with sugar absorption?

The soluble fiber in dried fruits forms a viscous gel in the stomach and small intestine. This gel physically slows the movement of food through the digestive tract and creates a barrier that delays sugar absorption into the bloodstream. The result is a more gradual rise in blood glucose and a reduced insulin response compared to consuming an equivalent amount of added sugar without fiber.

Can I eat dried fruit if I have diabetes?

Yes, but with careful portion control and pairing strategies. People with diabetes should limit dried fruit to 15–20 grams per serving, always pair it with protein or healthy fat (like nuts), choose lower glycemic options (apricots, prunes), and monitor their blood glucose response. Work with a Registered Dietitian or Certified Diabetes Educator to determine how dried fruits can fit into your personalized meal plan.

Are dried fruits safe for children?

Yes, but with important precautions. Dried fruits provide concentrated nutrition but pose choking risks for children under 4 years old. Cut dried fruits into very small pieces for young children and never leave them unattended while eating. Choose unsweetened varieties to avoid training young palates to expect extreme sweetness, and use appropriate portion sizes (15–20 grams for young children).

Conclusion: Making Informed Choices About Sugars in Dry Fruits

The distinction between natural and added sugars in dried fruits is fundamental to making choices that support your health. While the sugar molecules themselves may be chemically identical, the context in which they exist—within a whole food matrix with fiber, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, or isolated as empty calories—makes all the difference to your metabolism and overall health.

Armed with label-reading skills, an understanding of processing methods, and practical portion guidance, you can confidently navigate the dried fruit aisle. Prioritize products with zero added sugars, respect appropriate serving sizes, and pair dried fruits strategically with protein and healthy fats to maximize nutritional benefits while moderating blood sugar impact.

Remember that dried fruits, when chosen wisely, are not merely acceptable—they are valuable contributors to a balanced diet. They provide concentrated sources of dietary fiber, essential minerals like potassium and iron, and beneficial plant compounds. The key is treating them as the concentrated nutrition sources they are: enjoy them mindfully, in moderation, and as part of a varied, whole-foods-based eating pattern.

For more evidence-based guidance on incorporating nuts, seeds, and dried fruits into your diet, explore our comprehensive resources on micronutrients in dry fruits, macronutrient analysis, and common myths debunked. Continue your journey toward informed nutrition choices with our collection of specialized nutrition calculators and tools.

How we reviewed this article:

▼This article was reviewed for accuracy and updated to reflect the latest scientific findings. Our content is periodically revised to ensure it remains a reliable, evidence-based resource.

- Current Version 01/10/2025Written By Team DFDEdited By Deepak YadavFact Checked By Himani (Institute for Integrative Nutrition(IIN), NY)Copy Edited By Copy Editors

Our mission is to demystify the complex world of nutritional science. We are dedicated to providing clear, objective, and evidence-based information on dry fruits and healthy living, grounded in rigorous research. We believe that by empowering our readers with trustworthy knowledge, we can help them build healthier, more informed lifestyles.